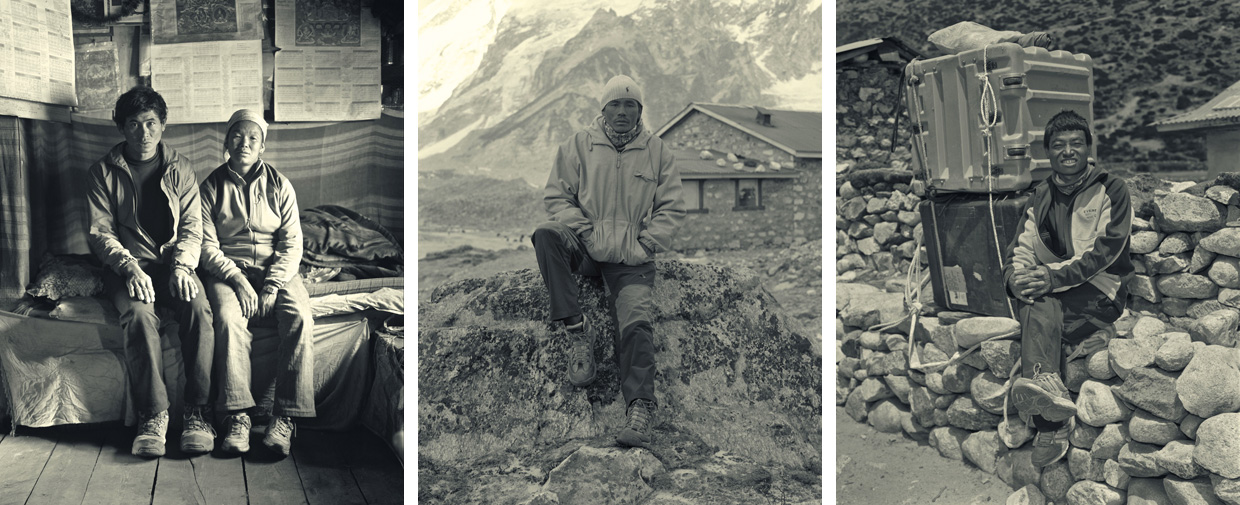

i porter

Rob Fraser

This question continually nags at me on the mountain trail, especially the parts that involve going up. Steep is the enemy and it is everywhere. In the Himalayan region it’s the porters who haul most of the gear for trekkers, climbers, hotels and lodges. The porters make the dreams of others a reality. Now – with almost 35kg on my back – I am trying out portering for myself; a 51-year-old pale-skinned, ginger Scot putting one foot in front of the other, gaining altitude on the path to Everest base camp.

It’s amazing what coffee, altitude and a sudden burst of fresh oxygen can do. Two years ago I was lying sleepless in a tent in the high Limi region of western Nepal. I wondered what it might be like to be a porter. They are everywhere on the trail yet their lives and their work largely goes unnoticed. I had a dream to see for myself what a porter’s life was like; I hatched a plan.

Two days below Lukla and this plan now seems way short of sensible. I’m sick, vomiting each mouthful I try to force down: noodles come out as they went in, but quicker. I’m wondering whether it’s ok to hire another porter (irony of ironies) to carry my gear, and for me to carry on walking the trail as a punter, carrying only my camera gear. I know every twist and turn on this route, every building and bridge, every peak on the skyline, having walked it 17 times. In fact, I know this region very well – as a trek leader for KE Adventure I’ve led more than thirty trips in the Himalayas over the past decade. But struggling along the path beneath a heavy load has revealed an entirely new perspective. Most of the time I am bent almost double and focused no more than three paces ahead of me. Looking up is a luxury.

I’m here because I had a dream to do it – I’ve set myself a personal challenge – and I want to get an insight into the lives of porters. I realise there’s no way to do that but to carry on; I have to keep face. But I have become a curio on the path. I am gawped at by porters and by trekkers from all over the world in equal measure as I amble along, like a stranded turtle in an oversized shell. Failure is not an option: pride and bloody-mindedness have become my favoured drugs whenever I hit one of my frequent lows. I’m stubborn, like a mule.

Struggling along the path beneath a heavy load has revealed an entirely new perspective. Most of the time I am bent almost double and focused no more than three paces ahead of me. Looking up is a luxury.

My mind-demons have been vanquished. I realise I am not a crazy fool and I can do it. I am in tune with the trail and the load on my back. At the same time, I feel a shift in attitude from the porters I am working alongside.

Porters in Nepal carry their loads, weighing anything up to an incredible 100kg (which I witnessed) using a namlo, which is a strap that rests on the front of their heads and around their load. If I had done this, I would have been a lot more stressed than I already am, maybe irreversibly damaged. I have had an old rucksack adapted so that it acts as a frame for the two client kit bags I’m carrying. It is working brilliantly, and I’m attached to it in more ways than one: I have even named it Vera in honour of the woman who painstakingly stitched it together. For me, Vera is a star. And it’s personal. Several Nepalese porters who have tried her have given negative shrugs: they much prefer using the namlo.

The Nepalese porters will have been carrying loads with a string strapped over their head for as long as they have been walking. Toddlers do it regularly, and the weight of the load increases with age. They have had a lifetime to adapt. My own adaptation needs to be quicker, but I’m getting there. By day eight of my 17 days on the trail I’m feeling a heck of a lot better. My first waking thought, each morning as I cross over the threshold to consciousness, has gradually shifted from ‘Oh God, not another day…’ to a point where I relish the challenge ahead.

By the time I crest the 4400m contour line at Dingboche – a large, potato-rich settlement that spreads across a narrow valley between Ama Dablam and the huge Lhotse Wall – my mind-demons have been vanquished. I realise I am not a crazy fool and I can do it. I am in tune with the trail and the load on my back. At the same time, I feel a shift in attitude from the porters I am working alongside.

Early on, it was mostly a case of strange looks and physical distance. Now, they have started to integrate me into conversations, are quite happy to walk with me and they rest and wait with me whilst I get out the video camera. A few times I have slept with them in their lodges – often a large single room with one or two extended single sleeping platforms where cards are played and the potent liquor rakshi is supped, before the bed rolls are laid out for sleep.

‘We have to pay for our own lodgings and the food is very expensive,’ says Robeen Tamang. ‘Most porters I know only eat one meal a day to save money’. This point was emphasised by Pasang Noru Sherpa, who has been portering for ten years: ‘Some companies pay 1000 rupees a day, but now I am getting 750 rupees. I have to control my eating. If I buy morning and evening meals then 750 might not be enough. In the morning I have just cheap food then I will have a big meal in the evening.’

When I drop the bags for the final time I announced my immediate retirement. But most porters do at least two treks a season, some manage three. Incredibly one young guy I met was planning on fitting in a fifth trip before the end of the trekking season in May. Little wonder that most porters who work in the hills are on the thin side of skinny, or as my mum would say about their legs: ‘I’ve seen more meat on a seagull’s beak.’

‘I am 35 years old and have been a porter for the past 12 years,’ said Pasang Doma Sherpa, one of a minority of female porters. ‘I will do this job for maybe another three years and then no more, I’ll be too old and tired. I am sending my children away, to good schools, to get education. Porter life is not a good life.’

When I reached the highest point and strolled into the lodge at Gorak Shep, the last settlement before Everest base camp, I was overcome with emotion. Not like me, I have to say, but I was tearful – I had set out with a dream, struggled, wavered, dug deep, and finally made it to the top. And all with the load of a porter. I’ve had a taste for the porter life and I agree with Pasang, it’s not a good life. Fortunately I had a choice. I chose to see what it was like, but only for one trek. I asked Man Bhadur Rai, the porter who was lugging my film equipment, if he was happy. His reply was typically Nepali, direct from the school of ‘it is what it is’.

‘What can I do if I’m not happy?’ he said, ‘I still have to carry. It’s difficult, I have no choice. It’s a hard life but I will work hard to get something out of it. I have a thought that I would like to walk with a light load, but I have no choice. My heart is heavy, but I have to try and make it happy’.

An exhibition of Rob’s images will be showing at The Royal Geographical Society in London between November 24th and 30th . Rob will be one of the speakers at the RGS Explore conference over the weekend of November 15th and 16th.

Website: robfraser-photographer.co.uk

Website: i-porter.co.uk

Twitter: @robjfraser