After The Dog Sled

Greenland Hut Life

Written by Tanny Por // Photography by Mads Pihl

A pack of dogs kick up the snow with their strides forward. There are only 35 more metres to go, but the hounds’ muscles are clearly strained. With their tongues lolling in the crisp, fresh air, they labour to pull a sled, a driver and its passenger, me, towards the top of the hill. A few more metres of pulling, and then finally, the panting dogs arrive. A crimson hut beckons, our lodgings for the night.

The well-trained Greenland dogs sit and rest, knowing instinctively that they have reached their destination for the day. After departing in the morning from the town of Ilulissat, it took us three hours to cross over snow and the frozen sea to arrive in Kangersuneq Bay. The dogs and musher sweated to get this far, but as my only task was to savour the dramatic landscape (and to try not to fall off the sled), I’m glad the opportunity for warmth is near. Icicles were beginning to form on my hair.

Historically, dog sledding once had but a single purpose: survival in winter. It allowed Inuit to be mobile, often enabling them to scour the ice for the next seal breathing hole where they would hopefully find their next meal. Greenland dogs are smart, com-pact and incredibly strong animals, and they are happiest when working. They each have their individual personalities: some are born leaders, some are lazy; some are friendly, yet others prefer to keep to themselves. But when they begin to run they be-come one seething energy machine.

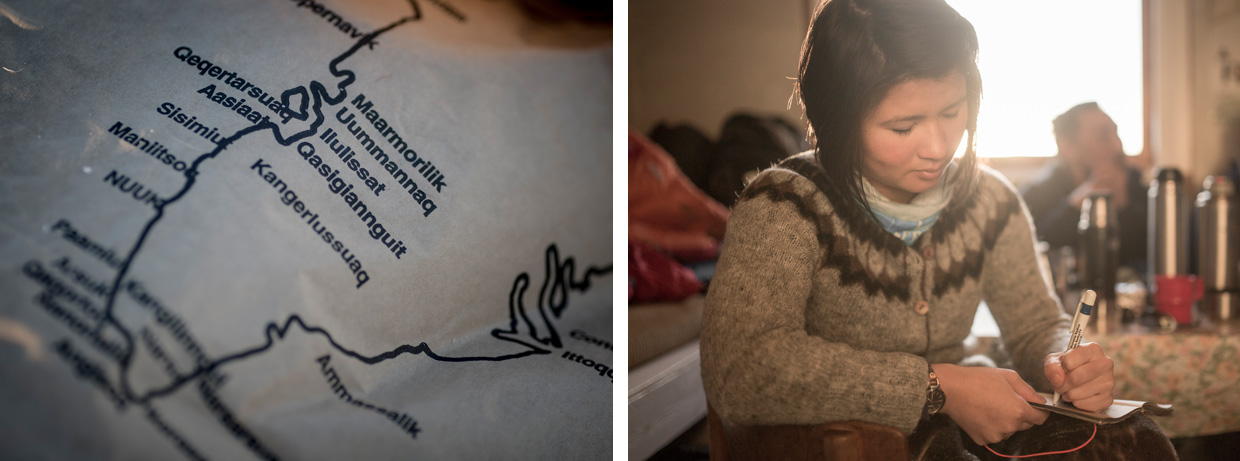

The terrain in the famous Disko Bay region in West Greenland is pure ice-sculpture in winter, and only accessible overland via snowmobiles and dog sleds. We are two visitors and two Greenlandic dog mushers. But for the presence of our wooden lodgings and the trails left by sleds, we might be forgiven for thinking that we are the first visitors to this remote land of ice. It’s a daunting thought. And for a first-time dog sledder like myself, one fact takes a moment to sink – those hills beyond the flat, snow-covered field are, in truth, vast icebergs marooned in the frozen sea.

We are, however, just following the everyday path of the locals. My Greenlandic driver, Niels, a fisherman and dog musher by trade, tells me that the locals travel dog-sled style to reach fishing spots that are only accessible in this way. But also, they make social calls to the nearest settlement by crossing the ice, go out hunting with a dog pack, and, of course, they just have fun with them.

Mushing is not the easiest lifestyle, Niels explains to me as we set up, but he knows no other way of living. Dog mushing defines who he is. The deep wrinkles lined on Niels’s face show how harsh the life is. Long days steering the sled dogs in the mountainous back country demand high physical energy. Mushers must become intimately acquaint-ed with this harsh landscape to survive. Niels tells me that places without names do not concern him, but I should remember those places that have been given names. There is a reason for a particular location to be given a name, whether it was thought one to be a good hunting spot, or possibly even a dangerous location. There is much meaning to a name, he tells me, and it is good to remember that.

Even though we are in nature’s thrall here, there are still many things to do to prepare our stay. The team prepare to ready their hard-working animals for a well-earned rest. As they walk back and forth around the camp, de-tangling lines and chaining the dogs up in groups, twelve pairs of canine eyes loyally follow the movements of each master. I look on amused – it’s like watching ping-pong at play. The relationship between these working animals and their master is a deep symbiotic one: they need each other, but the master sometimes requires complete obedience to navigate the harsh environment Greenland hurls at them. When the dogs are squared away, we work together to unpack and get the hut ready.

I don’t think that anyone has visited the hut for a while, as wind has piled snow at the entrance and thrown the chairs upside down on the terrace. Opening the door of the unlocked hut, the first thing Niels does is light a fire in the oven. It is frigid cold inside, and 30ºC below outside, but he assures me that the room will warm up quickly.

A quick assessment of our living quarters for the evening bestows the conclusion that it is a practical little space. A small sturdy wooden table stands in the middle of the room. It holds some old magazines, a tattered logbook and an oil lamp for the evening. In one corner there’s the kitchen area, with a big pot standing on top of a gas stove. And a sink with no tap. Across the room are some raised wooden planks with mattresses for up to four guests. All are in close quarters of each other. It will be a cosy stay. I check my phone, but realise that we are far out of reach of any signal. This befits the experience – being in such an isolated site, with only sea ice surrounding us and dogs to keep us company, everyday life as I know it seems all but left behind.

I finish the last sip of water in my bottle and turn instinctively towards the sink, before realising that the lack of a tap spout probably means we have to collect water from outside. Niels explains that there is a nearby freshwater stream stemming from a glacier. Unfortunately, like everything else, it’s been frozen now for many months.

Our diminutive group stroll over together, with a bucket and ice hack. Squinting with concentration, Niels slams the hack into the part of ice with the deepest tone of blue. The denser the ice is, he explains, the more water it will produce when it melts. Even at 30º below it is sweaty work. Ice chips fly about when the hack’s edge strikes the surface. One guide carves out the big ice chunks from the ground, while the other uses a smaller knife to chip it into smaller pieces.

I watch the team work together to harvest ice. Greenlanders seem to communicate between themselves very effectively without words. It is almost as though they can read the minds of one another, anticipating what the other wants without having to express it orally. Some drivers speak only a very simple level of English, but it’s easy enough to get by with limited words and gestures. I reach my hand out, and together Niels and I bear the bucket back towards home, where it will slowly melt into drinking water.

While one musher prepares dinner, the other explains that he will go hunting for small game over the next few hours. I seize the opportunity to head out for a walk on the sea ice. It still fills my stomach with butterflies to think that I’m actually walking on water. When I return to the hut area I hear the dogs howling before I see them. They are in frenzy, and I see that it is feeding time. The dogs lunge at the pellets thrown at them, and they frantically eat up as much, and as quickly, as possible. I make my way inside the hut.

All too suddenly, hours have passed and the light has begun to fade. Our fellow musher returns triumphant with some snow-white ptarmigan fowls caught in the backcountry. The hardest part, he says, is to spot the ptarmigan, which are very well camouflaged with its surroundings. He hangs the birds onto the rails of the hut outside saying that he will take them home to Ilulissat. They taste a bit like chicken, apparently, and the Greenlandic way is to boil it.

Inside the warm hut, an evening of sharing stories is on the menu. Our stomachs are also tended to, and bowls of lamb soup are wafting on the table. A glass of pure, melted glacier water quenches my thirst. Next comes sleep. And after long days in the freezing climate, a good night’s sleep comes easy. A couple of dogs howl just outside our hut, and I smile knowing that I am in Greenland.

Tanny Por grew up on the streets of Sydney, Australia and accidentally ended up in Greenland In 2013. Now everyday is an adventure. She tells stories about living (and sometimes surviving!) in Greenland’s capital city, Nuuk at www.thefourthcontinent.com. and @fourthcontinent.

Mads Pihl was once a social anthropologist but eight years in Greenland has transformed him into a bottom-up oriented content manager for Visit Greenland with a passion for photography. Find out more via his website: www.madspihl.com/ or follow him on Twitter @madspihlphoto

You can read more winter and dogsledding adventures at www.greenland.com. This trip is offered by Ilulissat Tourist Nature and sponsored by Visit Greenland.

Facebook: /ilovegreenland //

Instagram: @ilovegreenland //

Twitter: @ilovegreenland