Aftershock

Jonny Hawkins

I’m standing in a bookshop searching for an English-Nepalese dictionary when suddenly the ground below me starts to shake violently. I contemplate diving under a table as the quake intensifies, book after book tumbling down from the shelves all around, but a stampede of people carry me out of the door instead. There is mad panic in Thamel, Kathmandu. The road ripples and bends before my very eyes, bricks rain down from rooftops and an adjacent street cracks right down the middle. Total panic and fear sweeps the city. Confused, we follow the throng of people heading for a safe area, passing collapsed houses, crushed cars and deserted shops. A heap of rubble hides a buried man and twenty others are frantically shifting debris trying to find him. Dust fills the air. People are in total disarray.

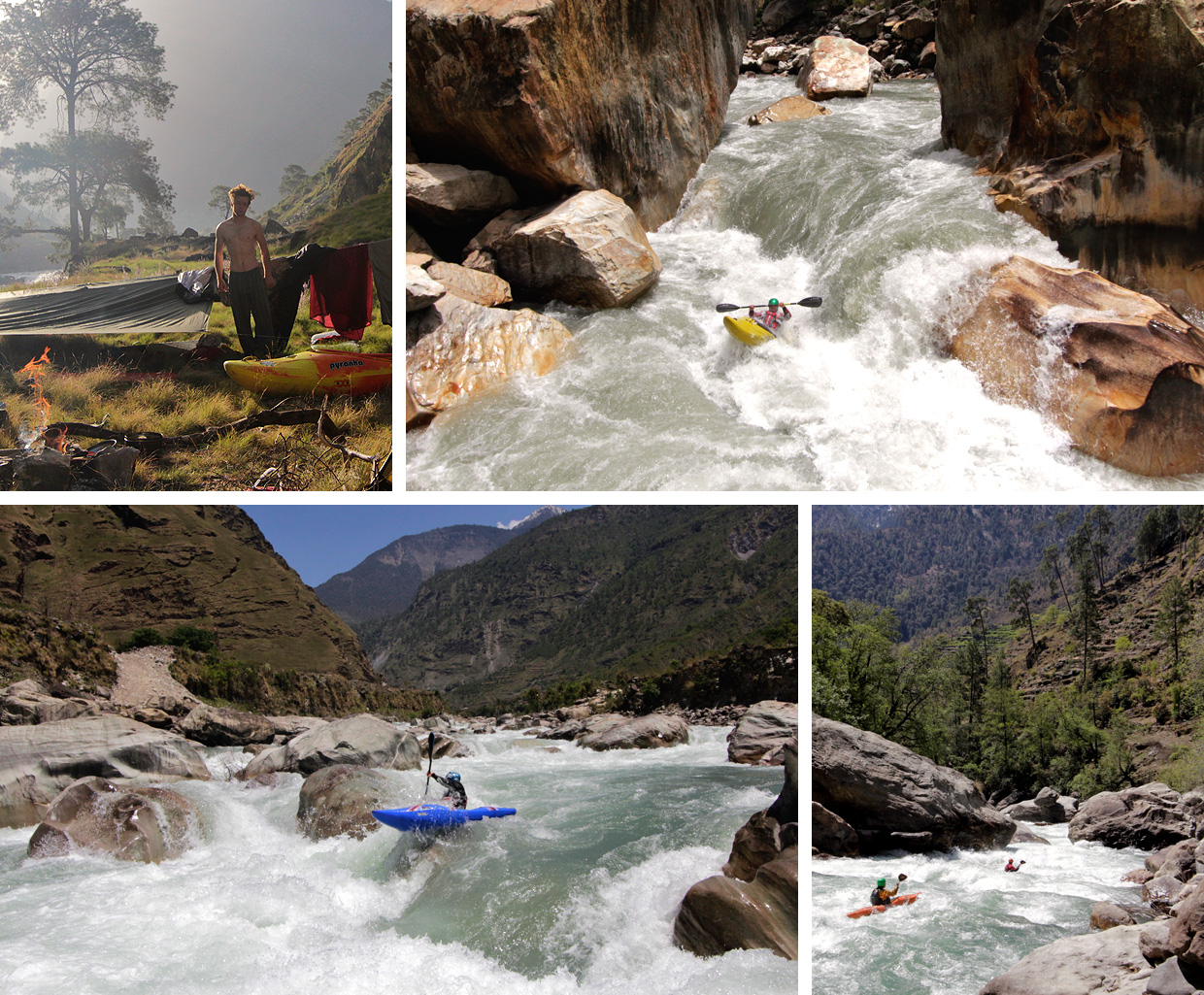

One week earlier I was midway through a 10-day kayaking expedition on the Humla Karnali, ‘one of the finest whitewater rivers of its length in the world’, with big plans for the next three months that would see me kayaking on rivers up and down Nepal. I had just been joined by friends Lee Royal and Rory Woods in Kathmandu and we were planning for our next river descent when the quake struck. Communications go completely down so we don’t immediately realise the full impact that this devastating 7.8 quake has had on the country. Instead, we spend that first night out in the open, strangely enjoy the communal atmosphere that surrounds us, blissfully ignorant of the thousands of deaths that have occurred right across the country.

The next day we take an internal flight to our next river objective, and it’s only after we’re en route– once we’ve regained internet access – that we finally comprehend the full extent of the devastation. Worried messages from family and friends flood our inboxes, whilst the images on the BBC are unbelievable. We plan our return to help with the relief efforts as soon as possible. After a flight into the remote Dolpa region and an awe-inspiring three day walk among beautiful mountains, we arrive at the start of the Thuli Bheri River.

We are in Peter Matthiessen’s ‘The Snow Leopard’ territory. Distant snowy peaks crown the stunning mountainscape, with manicured terraced fields leading down to the silvery turquoise river glistening beneath the sun. Children play amongst pecking chickens whilst goats roam all around. The beauty and happiness that radiates from this simple existence is wonderful. Hot and tired from the hiking, we enjoy the first ice cold splashes of river from our kayaks. Reaching these remote rivers is full of challenge, but the solitude and isolation of the journey makes it all worthwhile.

Distant snowy peaks crown the stunning mountainscape, with manicured terraced fields leading down to the silvery turquoise river glistening beneath the sun. Children play amongst pecking chickens whilst goats roam all around. The beauty and happiness that radiates from this simple existence is wonderful.

Flowing from the glaciers of the Upper Dolpo, the freezing river squeezes between narrowings in the bedrock and pours over rounded boulders. Eagles soar above us and children enthusiastically run down the bank as the whitewater picks up to unrelenting Class IV/V. We stopover in the town of Dunai, before continue our five-day paddle through towering golden canyons and past isolated villages as the river’s volume and power increases. This 114km river section is one of the finest in the world. It is difficult enough to require constant attention, but easy enough to negotiate most rapids from our boats, creating a challenging yet enjoyable journey. In the evenings we sleep under the stars, surrounded by majestic pine trees. We feel a million miles from the devastation of the earthquake, but a seed of regret lingers inside that we did not help immediately.

Caravans of jangling mules pass us, following the ancient ‘grain for salt’ trade route that winds down the valley. By the third day, the unrelenting power of the water has taken its toll. Tired and weak from mild ‘Nepali Belly’, I begin to make mistakes whilst following the more experienced Lee and Rory. I know that a small error could result in a horrible swim, putting teammates at risk whilst recovering all of my kit from the flow. I worry that I am holding the boys back but luckily the even stronger fear of swimming the rapids prevails and I portage some that the others paddle. By now the river has gained significant volume and slowly slowly, it opens out into wide shingly rapids that wash us down to our finish point at Devistal.

At least half of the houses have collapsed, with everyone sleeping outside for fear of an aftershock. We are stunned by the amount of destruction and question our objective of only helping one village amongst so many in need.

Exhausted, we get off the river and walk up to the town to get the terrifying night bus back to Kathmandu. We sleep for the entirety of the journey and immediately get in touch with our friend Daz on return. He runs a paddle-sport expedition company operating throughout the Himalayas and with his vast network of friends has set up a grassroots aid project. We agree to get involved immediately with a project delivering food and tarps to a rural village devastated by the quake. During the treacherous journey we pass countless destroyed buildings and upon arriving at the settlement are mobbed by thankful villagers. At least half of the houses have collapsed, with everyone sleeping outside for fear of an aftershock. We are stunned by the amount of destruction and question our objective of only helping one village amongst so many in need.

We divvy up the food and tarps into 27 piles and one by one hand it over to the incredibly grateful families. Some have lost everything – cattle squashed by their housings, food supplies ruined and family members killed. We met a man dressed in white, a custom carried out after losing a parent or wife. A mother and daughter collect their supplies with no male family member to help rebuild their home or go away to earn money. These encounters are deeply emotional and no doubtedly will stay with me for the rest of my life. We are showed round the devastated town and invited to eat dal bhat. We refuse but they insist, giving what little they have to show their deep gratitude for our help. This is a classic example of the Nepalese mountain people’s kindness and generosity.

On return to Kathmandu we pass through a particularly hard-hit village: the school is totally flattened and there is very little tin for families to rebuild semi-permanent homes out of. There and then we decide that it would be our next project. After a day to plan and prepare, Rory and I get the bus and then hitchhike back along the 4 x 4 road towards the village. Surrounded by locals, we get chatting to a boy named Sujin on his way to visit his family in Bombera. We soon realise that this is the town we are heading for. Upon arriving, Sujin shows us round, introducing family members and explaining how the earthquake has affected their lives. We meet one family still living under a scrappy tarp. The father, Shambuh, has severe asthma and only one son to look after the subsistence farm; the family is very poor. They immediately offer us tea and we get chatting, realising that this would be a very worthwhile family to help.

We set up our tarps and then eat dinner with them. Initially they refuse our help, insisting that we are guests and we can relax and enjoy Nepal. Sujin explains that we are here to help rebuild their home and they come round to the idea, explaining that we will be their sons during our stay. We are humbled and agree to buy some building materials to start work the next day. Trying to build a wood-framed house in two different languages is difficult. We both naturally have different ideas that we can’t share. The going is very frustrating and things don’t go well. Slowly though, we learn each other’s strengths and weakness and a design evolves. We learn important Nepalese words like; ‘hammer’, ‘nails’, ‘rest now’ and ‘work tomorrow’. Progress quickens.

As the days pass, we form closer relationships with the family. Slowly their shy and apprehensive behaviour evolves into deep friendship. The turning point for me was Shambuh helping me wash myself at the village tap. For deeply-seated traditional people such as he, this simple action represented true acceptance into the family and the forging of a lifetime friendship. Relationships strengthen and we are soon laughing and joking at our very British mistakes; our laps covered in dal bhat, calling a chicken a rat by mistake when thanking them for dinner, and making them endure our ‘lovely’ porridge all became running jokes. They teach us about their traditions and way of life, explaining their caste system, marriage and hopes for the future. After five days, the house is finished and it is time to depart. I hug Shambuh and sense his sincere gratitude, but also his fear for the coming monsoon.

We spent five days in a single village helping one affected family amongst thousands right across Nepal. Our impact, compared to that of the well-organised and funded NGOs and armies is minuscule, but for one family it meant the world. It seems there is a place for both grassroots and larger aid agencies, with the challenge being getting everyone to work together as efficiently as possible. As I write this from a backstreet café in Kathmandu, three weeks after the quake, the tremor of aftershocks still ripples through the city. This constant reminder of the earthquake’s power never leaves and with the monsoon approaching, hard times are ahead for Nepal. But the resilience, diligence and kindness of the population gives hope. Armies, NGOs and grassroots organisations are now coordinating effectively and long term support is planned. The suffering is by no means over, but I look forward to returning in a few years to see how well the country has recovered.