Beyond Blood Diamonds: Descent of the Moa River, Sierra Leone

Harry Cox

The Mission

‘We are tourists’ I repeated for third time to the man who was eyeing me suspiciously through the dense jungle surrounding a remote village, a few miles from the Sierra Leone – Guinea border. His English was patchy but two questions came clearly through the darkness of the jungle night, ‘What research are you doing? What are you looking for?’ It finally dawned on me that the word tourist meant nothing to him. I attempted to explain that we had come to witness the beauty of Sierra Leone and the warmth of its people so that we could return home and share our experiences with others. Slowly his furrowed brow relaxed and he took me by the arm proclaiming that I must come and eat with him in the village.

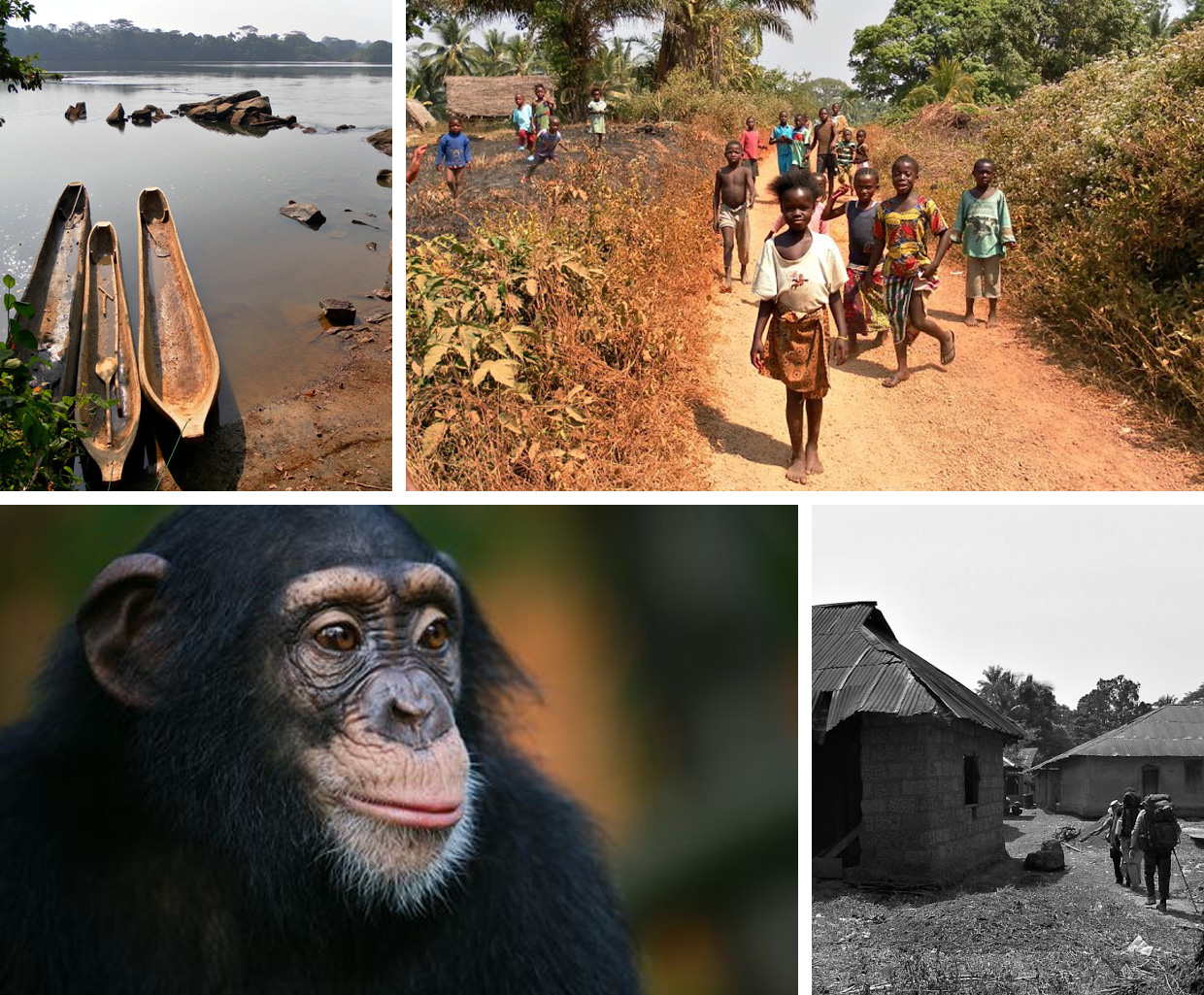

At times ‘tourists’ didn’t appear to be the most appropriate term to describe our group. Drawn from all around the world we had gathered in Freetown in advance of a 2 week expedition which would attempt to descend the Moa River by foot and local canoe, from the border with Guinea to the coast – a journey of just under 200km. The expedition had been organised by Secret Compass, a global expeditionary service who specialise in pioneering world first expeditions to some of the remotest parts of the world. As we shouldered our packs for the first time in an isolated village a few kilometres from the Guinea border and set off down a thin jungle track it was clear that we were embarking on an adventure into the unknown. After swimming across the Moa River into Guinea that evening it also became clear that we would make every effort to complete it fully.

The Journey

‘This boat is not new’ said our guide Abu as the canoe sank lower and lower in the water. Always loud and lengthy, the negotiations with local fishermen to transport us in stretches down the river proved to be relatively successful although at times the quality of boats left a little to be desired; hardly a surprise given that they had been designed for fishing! The precariousness of travel on the river was made abundantly clear on day 4 of the expedition when the canoe in which I was travelling was turned side on to a rapid and suddenly sank and disappeared in what seemed like an instant. Fortunately I was able to swim to the side of the river relatively swiftly, but fellow expedition member and passenger Nikki was not so lucky and was swept away in the rapids only to emerge 500m downstream, bedraggled but unscathed. In fact the biggest casualty of the incident were my boots and their loss forced me to spend the next day couple of days trekking in my sandals before I was able to buy a pair of trainers from a local motorbike taxi driver.

As we shouldered our packs for the first time in an isolated village a few kilometres from the Guinea border and set off down a thin jungle track it was clear that we were embarking on an adventure into the unknown.

The seriousness of correct navigation through these jungle paths were ominously impressed upon us after we were informed by a village chief that we could not proceed along our intended route because a secret bush society initiation was taking place. Sierra Leone is famous for its spirituality and the presence of these bush societies is an all pervading fact of everyday life for the vast majority of the population. It was made very clear that we were forbidden to venture anyway near the area where the initiation was taking place and we were just grateful that we had been allowed to continue at all.

The People

‘One of your brothers passed this way recently’ we were reliably informed by the village chief as we sought shelter from the baking midday sun in the sliver of shade offered by the rudimentary mud huts of the village. Our surprise, and slight disappointment at this piece of information, did not last long when, upon further examination, we ascertained that he meant 1992. This exchange pressed home a fact that was becoming abundantly clear to us as we journeyed down the Moa River, namely that very few outsiders had ever ventured this far into rural Sierra Leone and those that had were not there as tourists.

This reality made the welcome we received in every village all the more remarkable as we were immediately surrounded by a crowd of all ages before proceeding with the protocol which dictated that we first seek permission from the chief to hang our hammocks in nearby trees. Setting up camp often seemed to become an activity for the entire village to become involved with; some helping to clear the ground, whilst others filled our water containers from the river before watching with some bemusement as we dropped our chlorine tablets into the brimming bags. After we had eaten and were seated around the fire the ukulele, which was carried throughout the expedition by our very own wandering minstrel ‘T’, proved a constant source of amusement and fascination as we attempted to make our own contribution to Sierra Leone’s lively music scene.

It was becoming abundantly clear to us as we journeyed down the Moa River, that very few outsiders had ever ventured this far into rural Sierra Leone and those that had were not there as tourists.

The War

‘It’s strange walking through here without being heavily armed’ said Paul, our expedition guide, nonchalantly as we set foot on one of only 2 bridges to cross the Moa River in Sierra Leone. Having served with the British Army for many years, including in Sierra Leone as part of the IMATT programme to train the national army, Paul was not a man given to hype or over exaggeration and his words carried all the more weight for that. The 11 year civil war which plunged the country into chaos ended in 2002 and a decade on, our route would see us cross the region which had been at its epicentre and which had come to be heavily dominated by the RUF rebels.

Initially I found it difficult to reconcile the accounts of brutality, which I had read and heard about, with the friendliness and obvious peacefulness of the communities which we passed through. However the reality of the war was made real to us by our guide, Abu, who, one evening by the fire, told us of how he had returned from exile to rescue his mother during the war. The pair then spent weeks on end hiding in the jungle, living on unripe pineapples, as they desperately sought the safety of neighbouring Guinea. Whilst the thought that we were trekking down the same rough jungle paths along which child soldiers had once brought fear and destruction was disquieting, the unmistakable progress which had been made since the war was uplifting.

Relaxing on the stunning beaches of the western peninsular provided the ideal place to reflect on the experience of being part of the first group of travellers to journey through down the Moa River – undoubtedly a great privilege as we were able to gain an unparalleled insight into ways of life that have remained largely unaltered for centuries. We were also able to as encounter a Sierra Leone which was free from the shackles of its international reputation for child soldiers and mindless violence. Sierra Leone desperately needs more people to go and discover this for themselves.