Fine Lines

At the Fringe of a Comfort Zone

Jan Vincent Kleine

In celebration of the launch of the brand new Sidetracked Volume Seven, we’re releasing one story online from each of our previous issues. In this story from Volume Five, Jan Vincent Klein finds the edge of his comfort zone during a packraft expedition to Iceland.

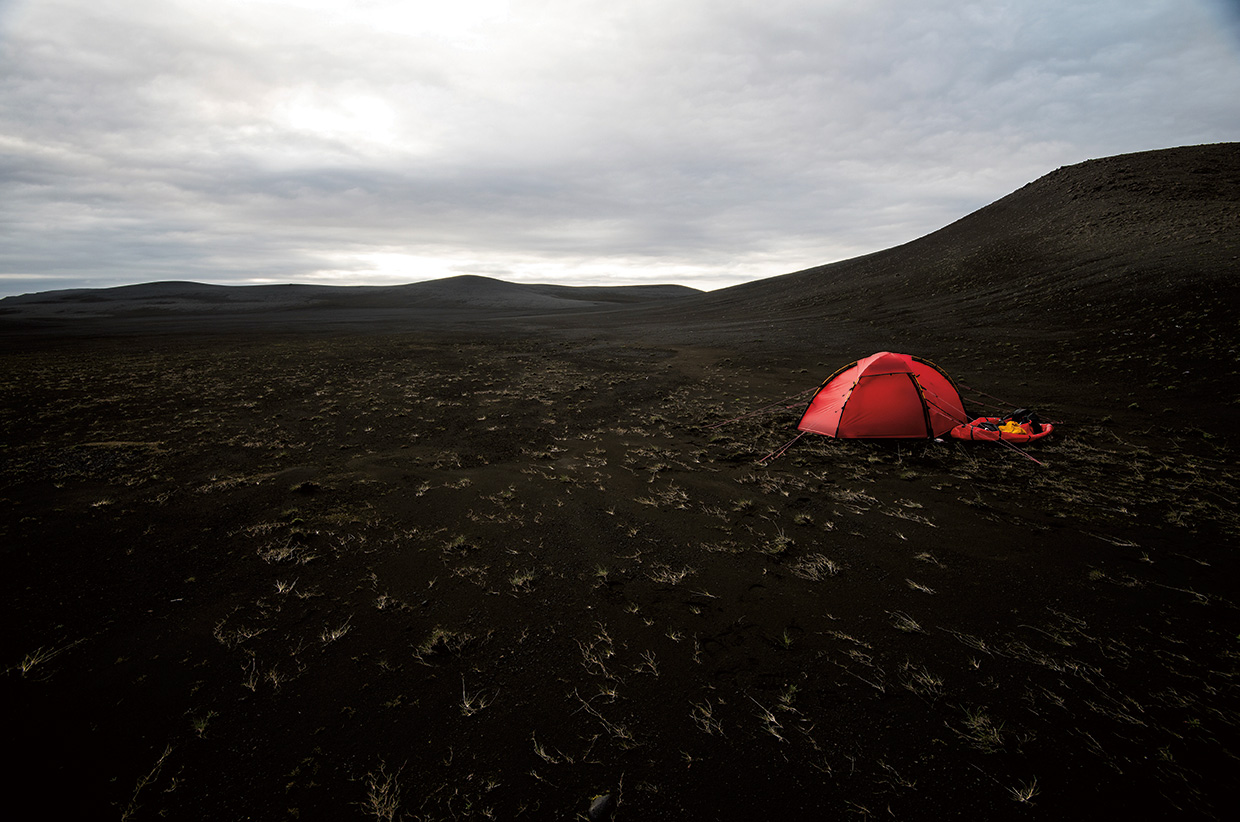

We quietly gaze out of the window, studying the world outside with a mixture of curiosity and respect. We are seated in the back of a large 4 x 4 that crawls forward across this seemingly lifeless desert on a rough track that is officially still marked as ‘impassable’. The last traces of any vegetation are far behind us. Throughout the journey I’ve harboured silent doubts that the landscape could become any more hostile than it already has, but I am proven wrong with every kilometre that the truck takes us closer to the starting point of our trip. Sand and ash buzz at the windows with a loud crackling noise and heavy gusts jostle the truck continuously.

When we arrive at the drop-off we are in the middle of nowhere. It’s 8.00pm in early July and the truck’s thermometer has dropped to low single digits. We are spat out into a miserable bedlam of wind, rain and sleet. Great.

Due to an unusually late spring, vast areas of the highlands are still completely covered in snow and ice. The prospect of high water levels due to snowmelt and obscured crevasses all scrawl ugly question marks next to many segments of our planned route. We want to journey as deep as possible into the backcountry and experience what we believe might be some of the most remote and desolate regions of the island. Attached to our backpacks are packrafts – lightweight inflatable boats that will free us from the territorial restrictions of uncrossable rivers and enable us to pursue our plan to link all four major ice caps of Iceland in a more than 400km half-loop, with a long rafting section down the mighty Tungnaá River.

My companion, Gerald, has considerable experience with water of all kinds. He explored the Okavango Delta in a dug-out canoe, has accompanied exploratory river expeditions in Guyana, Cameroon and Borneo, and used packrafts like the ones we are carrying everywhere from Australia to South America and the Yukon Territory. By contrast, I am a complete novice.

My inexperience with floating means of transportation is matched only by my curiosity towards it. My intention to secure at least some white-water experience ahead of the trip was thwarted when a climbing accident left me requiring tendon transplantation, ligament reconstruction and four screws in the ankle. This just four months prior to our departure.

Standing here now, at our starting point, staring into the icy, rocky wasteland that surrounds us, I am respectful of the challenges ahead and curious to discover how my rebuilt ankle will cope with the stress and hardship we are about to encounter. Yet, the prospect of this trip helped keep my mood buoyant during the challenging recuperative months that followed the accident. I’ve been looking forward to this re-entry back into the great outdoors for so long that I can feel the burden of my own expectations. I want this to work.

We want to journey as deep as possible into the backcountry and experience what we believe might be some of the most remote and desolate regions of the island.

This is why you are here, I tell myself. Leaving behind man-made paths and trails, creating your own interpretation of the terrain. It is an inspiring, but also a mentally demanding undertaking as the outcome is uncertain.

Of course there’s a whole host of physical, technical and navigational challenges to an exposed backcountry expedition, but I’m optimistic. To me the main qualification for undertakings such as this is a certain readiness to suffer – to endure hardship and take varying amounts of discomfort and pain with a smile. If I am not completely sure about my current physical fitness, I am absolutely prepared to suffer a little more if that proves necessary.

About 300 trackless kilometres later we are closing in on the Fjallabak. In the north-east the area is curtailed by a densely packed mountain range. When we reach the final pass it’s like a veil lifting right before our eyes, revealing a landscape tinted in red and speckled with snow and spots of crazy colours that stem from the volcanic activity in this area. It contrasts heavily with the black, almost colourless desert lands of the first two weeks. The view is breathtaking.

About a third of the route up to this point has been on a mixture of ice, firn and slush with the occasional river crossing as though the landscape itself desires variety. Consequently, both our footwear and feet have been perpetually sodden and cold since we set off two weeks ago. Both my big toes have suffered nerve damage due to frostbite and, to my dismay, are permanently numb by this stage.

Yet these minor inconveniences pale in the discovery that my ankle appears to be coping well with the stress and I am seeing strength and endurance return after being confined indoors for so long. In addition, a stunning vista such as the one spread out before us always helps to mitigate such minor aches and pains.

I wish we could relax to fully enjoy the view, but the way further along the main ridge leads to an arête down into the valley 200m below us that traverses a steep and treacherously exposed shoulder of loose scree. What appeared unimposing on satellite imagery now turns out to be an almost suicidal route in execution. The prospect of having to turn around for a full day, reverse back to where we started today to take an easier route that would delay our arrival in Landmannalaugar, and also our depot of badly needed supplies, doesn’t exactly lift our spirits.

This is why you are here, I tell myself. Leaving behind man-made paths and trails, creating your own interpretation of the terrain. It is an inspiring, but also a mentally demanding undertaking as the outcome is uncertain. You can never be quite sure if a projected line will in fact shape up to be a highlight, or a dead end. It’s a declaration of independence of the sort that brings with it freedom and self-determination. We empower ourselves to have faith in our own gut and our own reason. This feeling of freedom and personal responsibility can unleash huge physical and mental potential, but it can also unleash ill-tempered grumbling when that chosen line threatens to lead to a day of fasting.

I scout the unlikely possibility of a more direct way down. The whole side of this chain of mountains is furrowed into ridges and couloirs. They are all obviously and utterly impassable – except, I realise brightly, for one steep ravine that isn’t immediately recognisable as such. But we can only see the first third of the descent. About 50m down the slope the angle steepens, denying us any insight as to what lies beyond. Given the grim alternative we decide to descend and assess our chances.

We slide down the ever-steepening slope on a terrible mixture of loose scree sitting on top of several layers of very fine debris. All of it acts like well-oiled ball bearings between us and the solid soil deeper down. The whole ground moves with us, spinning and slipping away, taking us down without any effort from us. Initially, this almost feels like good fun, when the slide feels like it will come to an end easily. But the fun quickly turns into discomfort when we realise that we aren’t stopping and we can’t see what is coming next.

By now our scouting effort has taken us halfway down the descent. In front of us the steepness only increases once more. Beyond it, only metres away, we stare in horror as it leads into a snowfield that lies above the ravine all the way down to the ground. Unfortunately the little stream within our ravine has hollowed the area beneath the snowfield. It seems almost to hover above it, and we look down into a black hole easily big enough to slide into.

I am in front and shove some rocks down into the opening. They rattle down the slope inside the cave with a reverberating sound and don’t slow down before they get out of earshot. It’s terrifying. It appears there is no way down, but at the same time we realise now that we can’t possibly get back up the ravine on this steep, unstable ground. It slowly begins to dawn on us that we’ve gotten ourselves into a rather uncomfortable situation.

There is a fine line between daring and careless. Challenges make us explore the fringes of our comfort zone and frequently confront us with fear of our perceived limits. Overcoming these fears and achieving what may have once appeared impossible can certainly inspire confidence, determination and serenity in the long run. But it’s a thin line between this and pushing it one step too far.

With the way back up barred, I give in to an uncontrollable slide towards the entrance of the cave, tensing myself for the precise moment to jump. I leap and hang on to the snow – it holds – and relief floods my body as I realise I’ve done it. Gerald is able to follow a minute later. My hands are bleeding, my trousers and jacket are punctured, but none of this matters right now.

When we arrive at the valley floor it’s time for a little reflection. We made an obvious mistake by missing the point of no return, which hit us by surprise. But mistakes are made in the wilderness. How you deal with them and learn from them are what’s critical. After calming down, and chucking down some badly needed macadamia nuts, we put on our backpacks and continue our route south.

This story was originally featured in Sidetracked Volume Five

Jan Vincent Kleine is a photographer based in Hamburg, Germany documenting and creating stories about adventure, exploration and all the things that happen when you approach the outdoors.

Website: janvincentkleine.com

Instagram: @janvincentkleine

Facebook: /JanVincentKleinPhotography

Gerald Klamer

Facebook: /geraldtrekkt