Trabants At The End Of The World

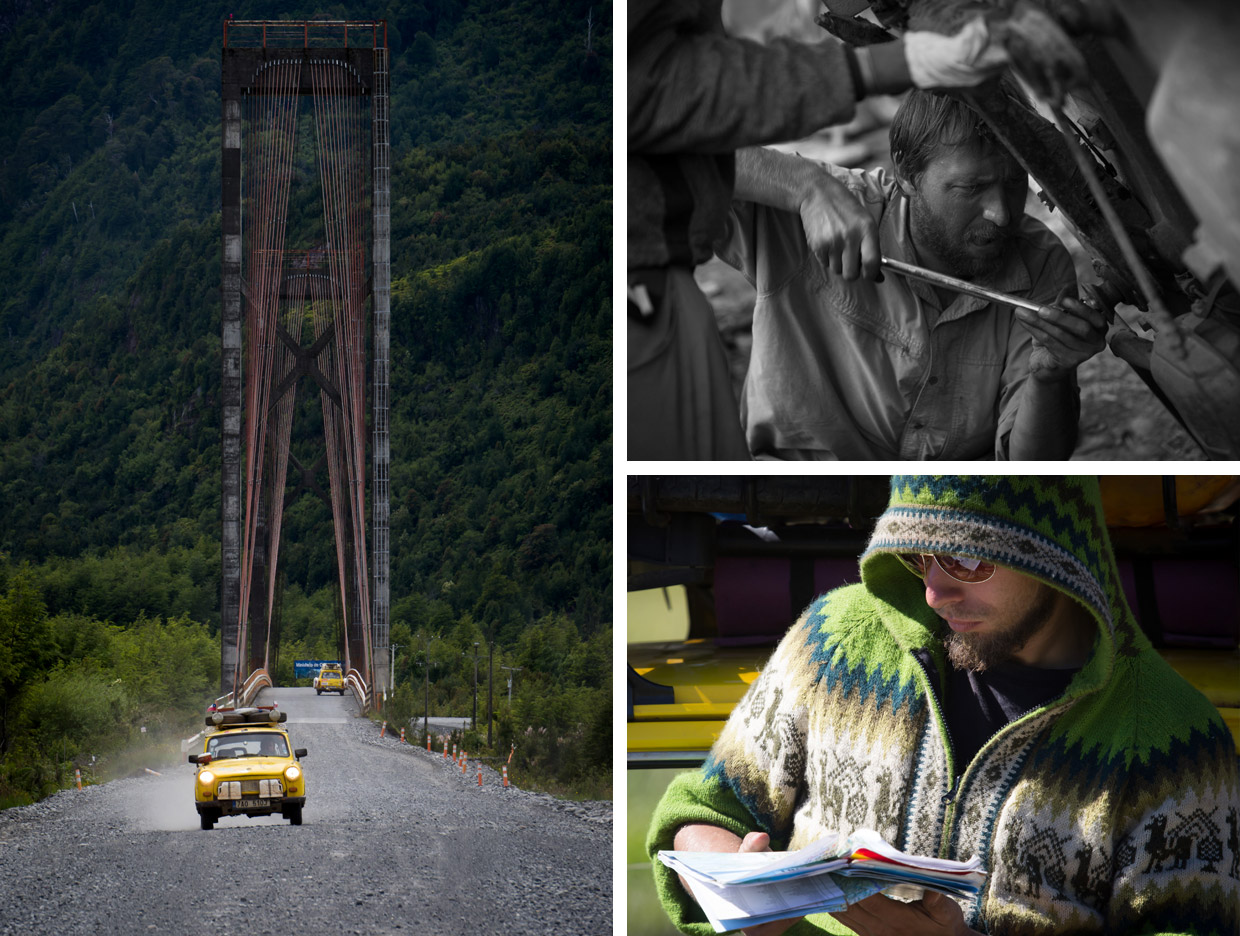

Dan Přibáň | Andrew Mazibrada

Photography by Jakub Nahodil, Zdeněk Kratky, Radoslaw Jona

Moat

Have you ever heard of Moat? I imagine not – only the people that live and work here really know anything about it. Yet it’s right here, a radar station at the End of the World. The southernmost point in the Americas which can be reached by car. Further south than Ushuaia, the archetypal pan-South American expedition destination; further south than Puerto Williams; and about 10 miles north of Puerto Toro, the southernmost settlement of the world, outside of the Antarctic, which lies on the island of Navarino.

A few meters below, at the foot of the cliff on which we stand, the Beagle Channel pounds ancient rocks and the bleached bones of dead trees. Whales attack humans here, that’s how wild it is here. A chill south wind is the only noise alongside the humming of the antennas of a radar station belonging to the Argentine Navy. It is the last outpost at the end of the last leg of our journey. An epic journey.

It Won’t Work

Sixteen and a half thousand kilometers across the whole of South America in two Trabants, a tiny Polish Fiat 126 Maluch and a Jawa 250 bike from 1957. We are Czechs, Poles and Slovaks heading into Guyana, Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina. What’s the point, you may ask? Well, asking that is just nonsense. We wanted one thing – to demonstrate that when you want something, you can achieve it. Fulfill your dreams and kick back at those who question you.

They told us that our group simply could not pass across the Amazonian rainforest standing in our way. They said that our undersized 2-stroke engines would not work over four thousand meters. We faced “death” roads on the side of mountains and a brutal drug mafia who might just take our lives for kicks. We laughed, outwardly displaying bravado but, inwardly, secretly afraid.

And now, peering at us, is the perplexed attendant of a radar station, the lighthouse at the end of our new world. We smile apologetically at him. After all, we have just entered a military installation with a motorised column that is anything but camouflaged. Instead of opening fire, he invites us further, perhaps stunned to see us and even curious. Inside is quiet and flooded with light. Antennas outside, the radar screen is all flickering flashes and he talks softly to himself, or into a radio, in Spanish and alongside the only person in this strange place at the end of the world, we brew tea. Outside, the wind buffets our small military building and the waves crash against the rocks whilst we play hot tin.

A few meters below, at the foot of the cliff on which we stand, the Beagle Channel pounds ancient rocks and the bleached bones of dead trees. Whales attack humans here, that’s how wild it is here.

Hands are glued to the steering wheel and if I wipe the sweat from my forehead I smear across it sticky red mud. It’s running down my neck, dripping from my forehead.

Battle With Bureaucracy

It was not entirely to be described as “fun” to get to here, even though the journey itself was almost always fun. In its own way. It was a battle to get our yellow cars from the clutches of Guyanese bureaucrats. The ship arrived only three days late, but the authorities would not let us have access to our container. You do not have the necessary paperwork, they said – we did, but they disagreed.

Tangled in a catch 22 of internal security processes, we sought an alternate route to our cars. We did not know who to bribe, so we wrote instead to the Minister for Tourism and the Chief Commissioner for Customs. We contacted local television and newspapers: even meeting with the President at that time seemed more likely than getting our Trabants, the Maluch and tiny Jawa from their prison. Finally, after three weeks of bureaucratic conflict we are successful.

Baptism Of Red Dust

From Guyana to Brazil there’s no highway conveniently stocked with gas stations. The temperature outside often climbs over thirty, humidity is stifling. All around are clouds of red dust: a fine crimson powder that seeps into everywhere. Hands are glued to the steering wheel and if I wipe the sweat from my forehead I smear across it sticky red mud. It’s running down my neck, dripping from my forehead.

This road wants to kill us. To thrash axles and batter us. Sometimes it is calm and we swim through clouds of fine white dust, smooth like a truck has crashed in front of us filling the road with powdered sugar. Dust or sugar – it all sticks equally well.

Our overloaded cars were not built for this – they suffer more than we do but they continue to fight and we with them. Once again, if someone asks me why I’m doing all this, I’ll tell him about journey called the Lethem trail – a journey through the jungle of Guyana where there is no asphalt. Because the real adventure is only where you have the chance of failure.

How To Pass The Impassable

The BR-319 is legendary. An impassable highway through the middle of rainforest. A road most are afraid to travel with challenging off-road sections. “No Pass” was the last thing we heard when we left the ferry. It did not sound encouraging.

Almost every day, as we collect kilometers on the BR-319, we look forward to coming out on asphalt. This part of the journey is hateful. The road finally closed in 1988 because even here they realised it couldn’t really be called a “road”. The thin layer of asphalt does nothing to prevent the cars sinking into potholes big enough almost to swallow a Trabant whole. Perhaps these are not even holes in the road, perhaps they are the valley itself.

Cars groan and creak like ships in a storm, inching along. Slowly, uncertainly, but we’re going. The chassis of each car pounds into the earth, overburdened by the weight of the equipment which we have installed. There is no right way here – all options are just as bad as each other.

Rainforest Terror

And then it begins – a notorious symbol of terror on the BR-319 – the bridges. New sits on top of old. At the feet of old are the ruins of even older. Picking aged planks we build. On these narrow cars we did not think the longitudinal beams would need to be too far apart. We are afraid because between them is a steep drop down to the river. We take pieces of wood from the water and mud to build with and then recycle them, slowly inching forward, one car behind the other, then the Jawa. Then we move on to the next bridge. Thankfully, most of the time, it doesn’t rain.

Then, the sky clouds over uncomfortably and without warning a demonic-looking front rolls in. The wind picks up. The sky stretches into ropes of rain. Lightning thrashes around us. Holes which were easily seen moments before are now camouflaged against the road, full of muddy water. Marek on the Jawa is drenched but passes everything. In the cars, it’s a competition for who can find the worse off-road sections. It’s evenly balanced.

The Altitude Record

We exit the rainforest after a week. Everyone is alive and all vehicles are quite serviceable. The next “A” is waiting for us – the Andes. We rush into it at full throttle. Sometimes, we even reach the giddy heights of 25mph. Collecting hundreds of vertical meters at a time, the altitude first comes to us in the form of dizziness. Chewing coca leaves helps divert the altitude sickness. We dip into the clouds, which we watched only a few hours ago from below. Then, it seemed to us the world ended. Four thousand metres and still we climb. The cars and bike are still going, albeit slowly. Sometimes, however, we even overtake a truck. The altimeter indicates 4500m – still climbing. Finally, the roads breaks over a ridge – 4,868m above sea level! No Trabant has ever been this high. We collect the record for cars with two-stroke engines!

And It’s Bad

Beautiful endless ocean greets us. After two months of traveling, we are beneath the Andes. We awake on a beach next to the Pacific. Traffic on the highway is brisk. We ask if we can get past to the next town. No problems, we are told. We make our way on the edge of two elements, wet sand as hard as asphalt, and water spraying in all directions. This is the life! Mark on the Jawa looks like an advertisement for freedom.

But driving in sea water does not agree with the internal combustion engine. The Jawa stops – initially slowing down and, eventually, we have to push start it. But this was not a good place to travel – the tide rises and wind gets harsher. Here comes the ninth wave, the ninth of nine terror sailors. Bigger, stronger, then bigger again… moments before the car was a good 20 meters away from water. Now the ocean rolls at them. With almost peaceful dignity. Brine, water and sand. Within seconds, the wheels sink again deep below the surface. Full throttle gets us nowhere, as if we are stood in curing concrete. We are digging with everything we have to hand. Water rises, each additional shovel-load is filled by the next wave.

We rush into it at full throttle. Sometimes, we even reach the giddy heights of 40mph. Collecting hundreds of vertical meters at a time, the altitude first comes to us in the form of dizziness. Chewing coca leaves helps divert the altitude sickness.

Pushing with all my strength, I feel like I am achieving nothing. The engine is screaming, but the car simply does not move. Another wave joins us and the tide is slowly rising. Needless to say, this is bad.

After more than three months, wandering traveler Dan Přibáň and his yellow Trabants accompanied by international Czech-Polish-Slovak crew with a tiny Polish Fiat and JAWA 250 whole South America from Guyana to America’s southernmost point accessible by a car – Moat radar station at the end of last path on the continent before returning North to Buenos Aires – 20,406km along the hardest and most beautiful roads that South America can offer.

Find out more about their journey via their website: transtrabant.cz

Andrew Mazibrada is an adventure travel and outdoor writer and photographer. He is a member of the Outdoor Writers and Photographers Guild and is Joint Editor for Sidetracked.

At The Last Minute

Pushing with all my strength, I feel like I am achieving nothing. The engine is screaming, but the car simply does not move. Another wave joins us and the tide is slowly rising. Needless to say, this is bad. The wind has picked up, we have stopped at the worst point in the arc of the bay, directly opposite the open sea. Another wave comes. We throw all the essential equipment onto the roofs as water rolls throughout the cabin.

We realise we can use the waffles, which we placed into the muddy Amazon. We have to get them under the wheels. The Maluch is the lightest and we lift him up to stand on solid plates. Full throttle achieves nothing. Another wave crashes in on us. White and swamped steam engine at its highest speed. Wave recedes again kick. Again lift the car. Desperate efforts and frantic pace, over and over. Eventually, after a herculean effort, you could say that we beat the ocean, but the truth is that, we just managed to stay out of his reach.

Was It Worth It?

The ocean is here again, but at a safe distance now, below a cliff at the end of the world. Dark brown and ice cold. Just like the wind blowing from the Antarctic. End of the World? Just rock above sea level, no banners, no memorial, no welcoming committee … Was it worth it?

We drove 16,578 km. We tried to break the speed record for the world’s largest salt plain on Salar de Uyuni, wandered around the Nazca geoglyphs, delighted in the most beautiful road in South America – the Carretera Austral. We tried to fight our way onto an active volcano and saw the collapse of a glacier. We watched a flock of parrots fly over us and palm trees and llamas run after endless pampas. We marveled at centuries-old Inca monuments and abandoned ancient cities. We met dozens of people who helped us and saw hundreds of people who waved to us and smiled when they saw us. The journey is the destination.