A Northern Playground

The Villmark Expedition

Written by Ian Finch // Photography by Emma Hall

We stood on the undulating hills outside of Bodø. On the slate-grey horizon Sjunkhatten National Park loomed like a jagged blockade of teeth-like summits. Immense fjords act as deep, impenetrable buffers to a colossal interior.

‘There’s a problem, a bloody big problem. Out there, where you’re going, there’s only one way in, maybe one way out. Us locals don’t even venture in that far.’

This was how the Villmark Expedition began, with dire warnings and scare tactics from a local guide in the foyer of our accommodation. As she scrolled through digital mapping software, we hovered over her shoulder, anxious and deflated, clinging to the hope she might say something at least a little ambitious about the region. No such positivity came. Like an infection, doubt bled through me. One of the expedition members, Jamie, had sculpted the route meticulously for us. His carefully-crafted map came from many hours of hard work. Days before the expedition started, we’d studied the route methodically with our photographer, Emma, and knew it inside out. But of course we hadn’t accounted for this additional information. There was no plan B. As the accommodation foyer fell suddenly silent, I bolted between optimism and indecision with each breath. The only noise I could hear was the scroll of a mouse wheel.

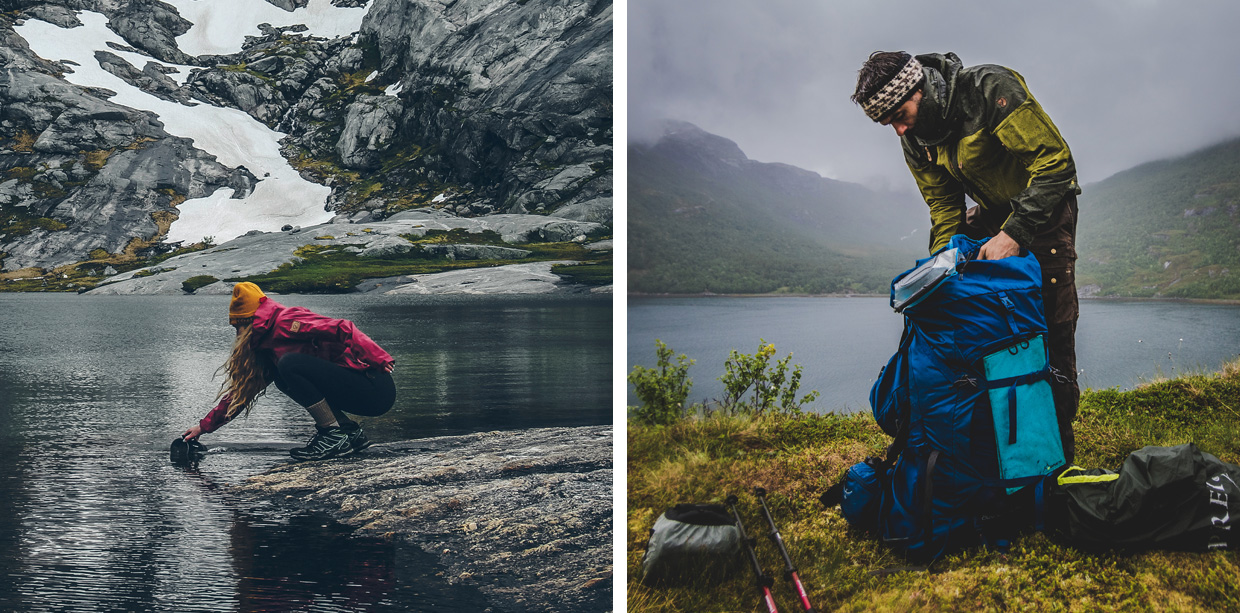

Those warnings still echoing in our ears, stooped beneath the crippling weight of our packs, we stood on the undulating hills outside of Bodø. On the slate-grey horizon Sjunkhatten National Park loomed like a jagged blockade of teeth-like summits. Immense fjords act as deep, impenetrable buffers to a colossal interior. The only known trail linking a coastal route to its remote ski-huts weaves a serpentine path through the south of this vast, isolated region. No other paths penetrated further, as far as we knew. Hidden valleys held saturated marshlands and small, glacial ecosystems. From aerial photography, we found that weather-smoothed, granite mountains stood guard, protecting an otherworldly land of forest, rock, and water. Cross-referencing our visual route with the Viewranger, we could see why nobody ventured into this fortress. It was cut-off. Desperately secluded.

The long trail along Sjunkhatten’s western coast snaked through tight birch thickets and wound its way up around small, glacial lakes. The tinkle of cowbells sporadically broke the silence as mountain goats appeared from behind summit boulders. As I picked my away along the trail, I watched the sun’s afterglow cling to nunatak peaks. Down to our west floated a coastal breeze, drawn into the valley by warm, rising air; swept across the landscape it knew like an old friend. This visceral beginning to our expedition acted as a mental buffer for the tough decisions I knew were heading in my direction. I’d learned the hard way to trust local knowledge and to ignore it at my own risk. Yet, with each step this foreknowledge worked against me: I simply couldn’t forget what we’d been told by that mountain guide. At night her words haunted me as I lay in the sun-drenched glow of my tent.

On arriving at the small cabin at Langnes, we were treated to a tapestry of beautiful, natural architecture. A small, red and black structure sat at the apex of an inland fjord. A trinity of granite pyramids channeled deep turquoise waters. We pitched our tents on a flat plateau above a calm, tidal bay, where spiralled seashells and deep-ribbed oysters clung to an ochre silhouette of floating seaweed, and where shoals of mackerel and bass danced in the shallows. To get to this point, we had slogged for two days from the upper reaches of northern Bodø. Our original route had envisaged taking us down into the sweltering, forested lowlands, then back up into the drenched, mountain glacial systems. Navigation became a constant, exhausting twenty-metre calibration. River-crossing after river-crossing forced us into a spiral of clothing changes and fatigue. Repeatedly, through boulders and streams, I would retrace our steps down the mountain in search of easier passage while Emma and Jamie huddled at the top, exhausted. I returned empty-handed on every occasion. The final stretch to the cabin, through shin-deep wetlands, had been the only relief.

At the cabin plateau, we studied the map in greater detail and sat together in a makeshift parliament. Optimistic thoughts and deeper concerns were aired. We could push up into the unknown with our still colossal packs, or sweep round to the south in a wide, possibly exhausting loop. From here, I had a perfect vantage point of the landscape ahead. Unseasonal June snow had packed in above 500m and the terrain looked unforgiving and brutal. The knock-on effect of this was to send glacial water to flood the lowlands during milder weather as it was now. There were no paths, and many dangerous scrambles, for the next two days. As I stood, surveyed, and debated, experience and instinct nagged me. Eventually I succumbed to intuition’s distant hum and made the call to backtrack and sweep south into a new mountain range, where wild reindeer were known to graze. Sadly, it meant dissecting our original route and shredding months of planning.

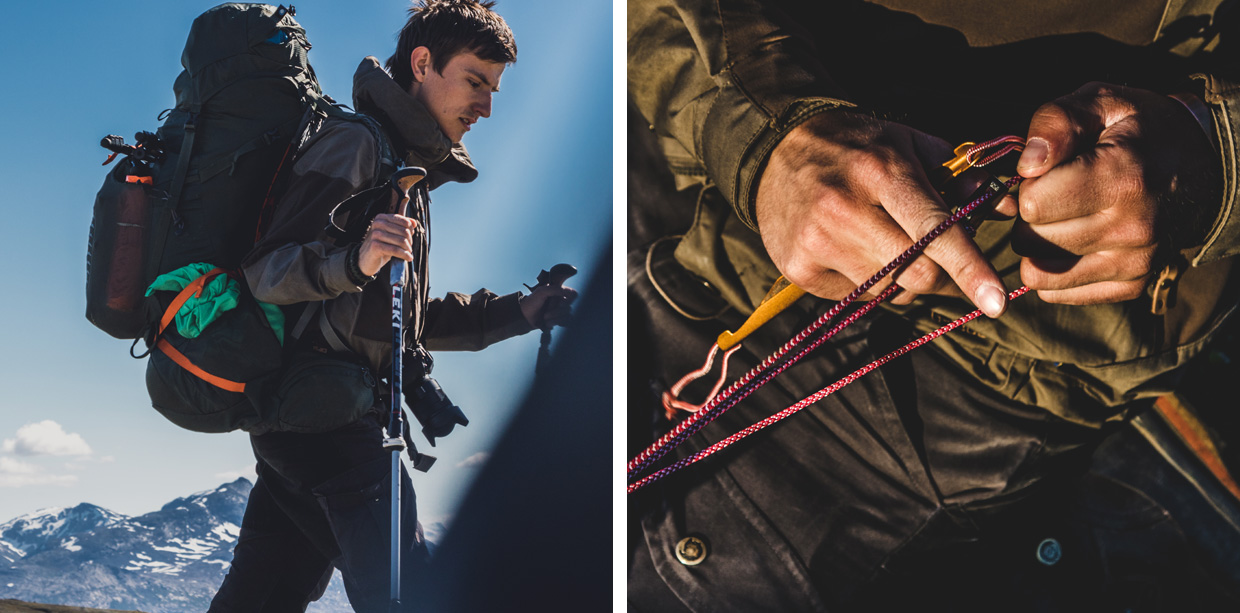

It took a full two days to make it to the high grazing grounds of the wild Norwegian reindeer. A triumph over near-vertical faces, mudslides, and thunderous waterfalls to reach this beautiful, elevated plateau. I took quiet comfort in my decision back at the cabin. The team had re-bonded in the crucible of their adversity, in the cradle of this new mountain range, and now our route would take us up the valley along the tracks of the reindeer. At its narrowest and highest, we would sweep down and to the right into its wet, fertile heartland. There, the warmth and comfort of two remote cabins at Lurfjellhytta, dissected by a glacial river, beckoned.

When I heard Emma’s scream time shuddered into slow motion. I swung round, seeing instantly that Jamie was missing. Emma, sprinting out of starter blocks, was nearly at an open crack between rock face and snow. I ditched my heavy pack as adrenalin wove a storm inside me. Sliding, barely able to maintain my footing, I found Jamie inside a crevasse, rucksack over his head and reaching upwards for fingers and hands. The snow had created huge slabs of melting ice on the valley floor. Streams had eroded the undersides of these ice packs, creating dangerous and fragile snow bridges. Jamie had broken off-trail and fallen into one of these invisible chambers. Through a storm of profanity, I reached down and took Jamie’s hand, hauling him upwards, helping him climb, until he lay beside me on the rock, breathing heavily. He was out of the crevasse, shaken but unscathed.

I swung round, seeing instantly that Jamie was missing. Emma, sprinting out of starter blocks, was nearly at an open crack between rock face and snow. I ditched my heavy pack as adrenalin wove a storm inside me.

As the cabins came into view, echoes of the crevasse incident focused my actions into preservation mode. Over the final two hours I pushed my companions on their pace and timings. Emma’s feet were dangerously wet and cold. Jamie, still unnerved by the fall, had slowly regained strength and resolve. The mountains, welcoming us with blue skies eight hours before, had tightened their grip with every passing minute. The conditions had spiralled into low visibility and freezing rain. We desperately needed the sanctuary offered by the shelters. As we approached the cabins, plumes of smoke drifted from chrome chimneys: they were occupied. Three female Swedish alpinists were in one, a family and friends in the other. They were bewildered to see two Brits and one American out this far, standing exhausted at the door. Dropping our wet kit on the floor of the entrance, we entered the sweltering living area despite their confused faces. A table and chairs were at one end, a sofa at the other. Socks dried high above a wood burner as it ate away at the logs on an almost nuclear heat setting. Rooms of wooden bunk beds, mattresses and duvets branched off the main area. Windows like a lighthouse offered a 360-degree view of the vast Norwegian wilderness we had just crossed.

I listened intently as he spoke, realising it was finally time to leave my bruised, stubborn ego at the door beside my sodden rucksack. For the second time I reluctantly resolved not to commit the team to the original plan.

That night a map covered almost the entire table. Thomas, a Norwegian with considerable experience of the region, hovered over one corner, I hovered at the other. Jamie listened to our conversation with a stern eagerness. ‘Where you plan to go,’ Thomas explained, ‘roads are cutoff, there is deep snow. The pass is closed.’ I knew what came next and I didn’t want to accept it. ‘You can try, but without experience of this area, it will be bad.’ I was right back in the foyer at the accommodation, anxious and deflated. We sat for hours. I fired back options, timings, and optimistic alternatives. The deep sigh, the scrunch of his expression, told me everything I needed to know. In Norwegian he debated our proposed route with his climbing partner. Again, he presented us with warnings and shrugged shoulders. To them it was a matter of inaccessible paths, weather conditions, and simply timing in and out. We might even be killed.

I listened intently as he spoke, realising it was finally time to leave my bruised, stubborn ego at the door beside my sodden rucksack. For the second time I reluctantly resolved not to commit the team to the original plan. I’d have to shakeout and re-route us once more. Their safety and mine was too important. It was though the wilderness had us on a leash, letting us go only at its pace, hauling us back if we surged forward. Toying with us. Both fists knuckle down on the map, pale and tight, I looked at Jamie. We both knew it: bar a few days of descent into the lush, glacial valley, this was the demise of our expedition. All the effort and money; we’d come so far and pushed so hard only to be turned back again. Energy drained from me. I made the final decision to end what remained of our Villmark expedition.

In the comfort and security of London, I now drift back to consider what I might have done differently. This thought process is an essential component of progression and learning; a form of therapeutic evaluation. Some may say it’s natural to balance the equation with benefits and drawbacks. Others might see it as over-thinking. Whether it follows success or failure, turning results inside-out exposes lessons required for growth. That’s always positive. Yet in these quiet moments, why am I still burned by guilt? That needs an altogether separate evaluation. Internally, I feel I let them down by suggesting and supporting both re-routes. There are so many unanswered questions and variables. What I do know is that my decisions, based on hard experience, fractured and changed the course of a bold journey. But I am comforted by the fact that everyone came back alive.

To me, as a leader, that evaluation is the right one.

Ian Finch is a cultural researcher who’s been passionately travelling to remote environments to learn about 1st nations communities for over 4 years. His endeavours are regularly filmed and shared in an attempt to inspire and educate about people in far away regions.

Website: ianefinch.com

Twitter: @Ian_efinch

Instagram: @ianefinch

Facebook: /Ianefinch

Emma Hall is a naturally curious person, who always strives to explore new places and activities. She is currently based in Seattle, although set to embark on new adventures soon.

Website: efrancis.work/

Instagram: @efrancisadventure

Facebook: /Emma.Hall

Jamie Barnes is an adventure videographer, photographer and video editor based in Hertfordshire, who always strives to share his adventures in the hope of inspiring people to get outdoors and reconnect with the natural world.

Website: jamiebarnesuk.com

Instagram: @jamiebarnesuk

Twitter: @JamieBarnesUK

Facebook: /Jamie0208