Being able to use the row as a platform to tell people about the tragedy of slavery and trafficking is a wonderful thing and perhaps will inspire others to dream big! I found a person inside me I didn’t know existed until Post St Charles in Barbados.

Julia Immonen comes from the world of sport and media. As an avid sports fan and athlete, she has found her dream job at Sky Sports News.

Julia became passionate about the injustice of human trafficking 3 years a go, an initial half marathon turned into rowing the Atlantic Ocean and founding Row For Freedom.

She is the founder and director for Sport For Freedom, a charity who rescue, rehabilitate and provide safe housing for victims of human trafficking throughout Eastern Europe.

W: sportforfreedom.org/

T: @JuliaImmonen

Andrew Mazibrada is an adventure travel and outdoor writer and photographer. He is a member of the Outdoor Writers and Photographers Guild and is Joint Editor for Sidetracked.

W: www.journeymantraveller.com

T: @JourneymanTrav

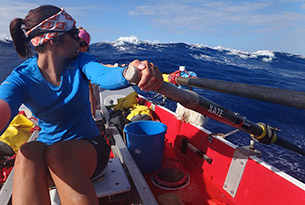

The coming weeks would see us experiencing seriously challenging conditions. Frequently, we surfed 50 foot waves in torrential rain. Within moments, then, the ocean would relax reverting instead to calm serenity. In truth, despite the danger and concentration, surfing waves actually got us further, quicker - the calmer waters were like rowing through molasses. I remember my first impressions of the boat being how highly technical it looked with all the wiring, electrics and equipment - Yet, if it could have broken, it did. We were called on to fix nearly each and every technical item aboard at some point – and of course usually in the dead of night. I seem to recall everything by days for some reason, It was deep into day 15 when the machine which desalinated the sea water into drinking water broke. We then had to hand pump water for a month. We were so careful with the hand pump because without that, we would have had to call for assistance which would have meant our records wouldn’t count. It took 2 hours to pump 2 litres of water, and so we all had to adjust to limiting our water intake - not ideal as we were dehydrated and expending a lot of energy. And the further south we went, the hotter it became. We added lots of (Dioralite) salts from our medical kit which was also an excuse to taste something with flavour. These became like gold dust with us all experiencing banging headaches with dehydration.

Physically, it was gruelling. My hamstrings ached all the way across; my wrists were constantly bruised and the chaffing in areas I do not care to speak about bit like knives. Sea sickness, one of the most virulent and horrific experiences I have ever had to deal with, lasted for a week although one of the girls had it for 30 days. We had to be creative with our clothes, adapting to the conditions as they changed. It is overwhelming to think of rowing 3,000 miles, not knowing how long we’d be out at sea and thinking of the 50ft waves were terrifying. I had to break it down. I would literally take it watch by watch, and when it got really hard I would take 27 more strokes, for the estimated 27million trapped in modern day slavery. It made my pain pale into insignificance when I remembered the stories of the girls I had met just weeks prior to setting off. One of the girls was rescued just a few days before I met her, her eyes were soulless, without hope. I had to keep going for her. I had a lot of time to reflect on the passion for this cause which brought about our campaign. I often thought about the millions of slaves who were transported across the very waters we were rowing on and the horror of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. Knowing I had the freedom to get off the boat in Barbados when millions today don’t, made my pain pale into insignificance.

On day 33, dolphins drew alongside the boat and scrutinised us with the curiosity of children. In fact, I felt that throughout our time we were experiencing nature at some of its most raw. The bright starry skies buoyed me and I found that when pushed to the brink by exhaustion the buzz of seeing a shooting star arcing across the heavens was enough to keep me going. Sunsets and sunrises, unadulterated by concrete the trappings of human existence, were breath taking. The further south we went, the hotter it became. In fact, far from being a blessing, it became so hot as to be unbearable, particularly as we had to restrict our water intake because we were hand pumping all the water. Most crews use para-anchors in the high seas to stabilise, but because we were aiming for the speed record, we carried on rowing through the serious wind which required huge concentration.

We rowed into Port St Charles in Barbados at 11pm on day 45. I would row the ocean again for the elation of that night! It was incredible to see our friends and family again. Having spoken to many adventurers, cravings seem to kick in and I craved orange juice with bits all the way across. That first taste of it felt for all the world like we’d succeeded. We felt so proud to actually have done it. No one wants to hear of five girls who nearly rowed the Atlantic, and so we knew the journey had just begun, in many ways. Being able to use the row as a platform to tell people about the tragedy of slavery and trafficking is a wonderful thing and perhaps will inspire others to dream big! I found a person inside me I didn’t know existed until Post St Charles in Barbados.

Don't miss out. Sign up to receive free monthly email updates from Sidetracked here.