Surviving the Great Depths and Swells of the Pacific

Survive Photo: Ben Moon.

Photo: Ben Moon.

In conversation with surfer and free-diver Hank Gaskell

By Viola Gaskell

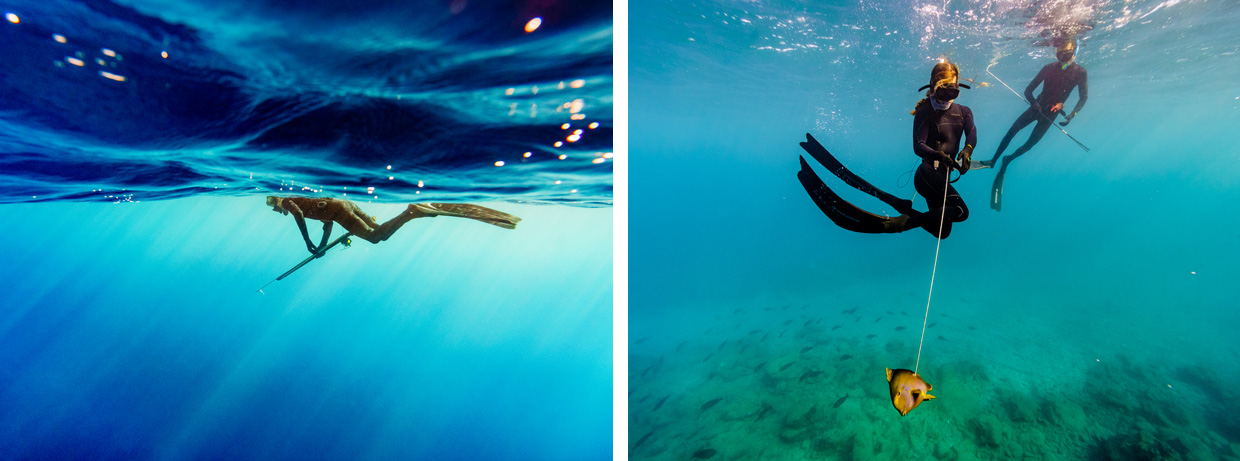

The average physically fit person can hold their breath for 60 seconds. Underwater, the pressure that compresses the lungs decreases that to 30 seconds. While diving with Hank Gaskell, he tends to disappear into the darkness of the sea only to return two, maybe three minutes later, often with a freshly speared fish in hand. ‘If I am resting underwater, I can manage four to five minutes, but if I am stalking a fish, that uses up way more energy,’ Hank says.

This capacity to hold his breath is a result of the thousands of hours Gaskell has spent in the sea. For years he was ranked within the top 100 surfers in the world as he travelled to surf breaks in South Africa, Indonesia, Brazil, and many more to compete in the World Qualifying Series (the WQS).

Gaskell grew up surfing and diving in a remote town in Hawaii of no more than 2,000 people, though it’s been growing way too fast these days according to him. Surfing has led him to more countries than he can count and landed him in some of the more threatening situations known to man. Freediving is his personal solace, the introspective act that has taught him to know his own boundaries with a solidity that keeps him alive.

In July, Gaskell attended a Big Wave Summit on Maui, home to Peahi, one of the most gargantuan surf breaks in the world, known to the outside world as Jaws. The summit was lead by Greg Long and Danilo Couto – two men who have made it their life’s work to surf waves that define what human beings are capable of in their sport.

I recently spoke with Gaskell about the Big Wave Summit, diving, breath-holding techniques, the surf industry, and what is most important to him these days. Here is what he had to say:

What techniques have you learned about holding your breath for long periods of time?

I practise a couple of deep breathing patterns, usually the Wim Hof breathing method (controlled hyperventilation and breath retention) and different yoga patterns. Most people don’t realise that it is often not so much the lack of oxygen that is lethal right away as it is the build up of CO2. It acidifies your blood and your body will shut down pretty quickly when that happens, so the prolonged exhales are vital.

At the Big Wave Summit recently, I learned a great one for relaxing your body while you are waiting for a wave by breathing in intervals of 1, 2 and 3. You breathe in for 3 seconds, hold for 6, then exhale for 9, or you could do 5, 10, 15, whichever set works for you. I used it on a surf trip in Indonesia recently, and it’s a great way to oxygenate your blood while resting.

What were some of the other tactics you learned at the Big Wave Summit? What do you normally do to stay safe in big waves?

We learned first aid techniques like CPR and tourniquet care, and we practised jet ski and surfboard rescues. We watched videos of situations that went terribly wrong and assessed what could have been done to produce a successful rescue. There was talk about nutrition and eating light for optimal performance. One speaker recommended beets because nitrate-high foods supposedly give your vascular system a boost.

Usually, I do warm-ups on the beach such as stretching and deep breathing. There are a few great stretches you can do to expand your lungs; I do backbends, and twists, and breathe deeply while I stretch. When I’m out there, between waves, I do the interval 1, 2, 3 breathing. I try to stay focused and know the lineup to make sure I’m in the right spot when a set comes.

Have you had any experiences with either surfing or diving when you thought that you were in real danger?

Surfing, I was out at a break called Phantoms on the North Shore and I caught the first wave of the set, didn’t make it and got thrashed. After that initial hold-down, I got pounded by a relentless set of 12–15ft waves. I’d come up and get a really short breath and be so winded I could hardly inhale – by the end of it I was so weak I could hardly climb on my board. Luckily the set ended. That was kind of a wake-up call.

Diving, I had one shallow-water blackout and my friend Marlon rescued me. I wasn’t too worried; we were watching each other closely and he is a great diver. I was conscious but my throat had closed up and I’d lost control of my motor functions. I did what’s called a samba – where you start convulsing for a few seconds – and he just held me until I came to and my throat opened up again. I probably would have drowned if he hadn’t been there, but also I would not have pushed it that hard if I hadn’t been diving with someone I really trust.

What did you learn about yourself from these experiences?

I think experiences like that trigger a little more gratitude. It leaves you feeling thankful for your life when you’ve just come that close to dying. It is definitely a lesson – you know where your limits are afterwards, and you respect them like your life depends on it – because you know, quite viscerally, that it does.

I know you’ve lost a friend to diving. What do you think that does to the diving community on Maui?

It made us all more conscious about practising safer diving. Losing such a great human being was a really hard reminder that it’s not worth it to push yourself that far. It can happen to the best divers. Jeff, who passed away, was diving with a friend but they were in such deep water, and the current was pretty strong so he couldn’t make it down to rescue him in time. A deep-water blackout is unusual. Most of the time it happens near the surface and you can save your dive partner – in a way, the more you advance, the more you open yourself up to dangerous new physical possibilities and the results can be tragic.

What advice would you give a beginner freediver?

Be safe. Take it slow and have fun, don’t push yourself too hard in the beginning, go with someone who is more experienced. Spend twice as much time on the surface as you do underwater. So, if you do a one-minute dive, spend two minutes on the surface breathing normally. That technique is supposed to let your body flush out the CO2 and oxygenate your blood to protect you from shallow-water blackouts. Try to be as relaxed as possible; take long relaxed exhales to achieve longer breath holds.

How do you mitigate risk when diving alone?

When I’m alone I don’t push myself to where I think or know I can go. I’m extra careful about shallow-water blackouts, I take it slow the first couple of dives, and ease into it. If you dive deep right off the bat, you can get really light-headed, so my first few dives are only 10 or 20 seconds. I am more mindful of sharks too. If I shoot one fish, I’ll usually go in right away.

Do you think that diving is naturally suited to you physically or mentally? How about surfing?

I think that as a pretty calm person, diving suits me. Doing yoga growing up taught me to be focused and to be intentional with my movements, which really complements diving. I naturally have a slow pulse; generally, the lower your heart rate is, the longer your underwater intervals will be.

When I surf and my heart rate is up, I metabolise air quickly, and it is difficult to stay calm. While paddling, your heart rate goes up a lot, so by the time you are on the wave, you are already in a position where it will be more difficult to hold your breath if you get held under. Some surfers can hold their breaths really well while being pummeled by whitewater, but I find it difficult to stay calm in that situation so my holds aren’t so great. The ability to stay calm under any circumstances is a lifesaver in big waves.

What is the biggest wave you’ve ever surfed? What did it feel like?

I’ve surfed waves with a 25ft face at Peahi, Waimea, and Phantoms. It’s amazing, and extremely difficult to describe – I think you have to do it to understand it. You get a crazy rush, when you are going so fast and there is all this turbulence around you and you don’t know if you are going to make it. You just push yourself and try to go as hard as you can go while understanding the ocean around you, and then instinct takes over and your body knows what to do because of all the practice you’ve put in. You don’t have time to think. It is about as present as I know how to be – standing in a big barrel. It’s pretty zen for me.

How do diving and surfing affect your mental state differently?

They are similar in a way, but I think surfing is more energising, and diving is more introspective. With surfing you are interacting with the outside world more. I love the way it clears my mind and energises me at the same time. Being out on a perfect day with friends is about as good as it gets for me. When one of us gets a gem, the rest of us are just as stoked for him or her as we are when we get our own perfect wave. It just creates this shared experience that is unlike anything else.

With diving, it is silent. You can’t hear, smell, or taste much, and your vision is restricted – what you see falls away within 100ft or less depending on the visibility, so you only have your immediate surroundings to contend with. When I start to relax into my surroundings, I notice so much more about the ocean floor; what is right in front of me becomes very sharp and intricate. Like watching an octopus move across the sea floor, that’s pretty wild. The sense of calm I find in diving is really special to me. It is like a mediation in a way.

What is most important to you at this point in your life?

My family, my friends, and my dog. You can’t go wrong with that. The endless pursuit of being the best person I can be, and learning more about how to optimise my life, how to squeeze the most happiness out of it – I think that is the purpose of life. One of these days I want to have a fully self-sustaining farm and garden with chickens and bees and solar power. I am already moving in that direction, but I’ve got too much wandering to do for now.

Follow Hank on Instagram @hippiehanahank // Written by Viola Gaskell: @violajgaskell • violagaskell.com

Photography by Ben Moon & Christa Funk