Trail of Tears Update Two: Where Rivers Collide

From The Field

Words: Ian Finch // Photography: Ian Finch & Jamie Barnes

Approaching the flooded Mississippi, we heard warning after warning about its dangerous flow state. Waters were unseasonably high this year as record rainfall and snowmelt from towards the source thundered downstream, submerging structures and ripping trees from their banks. It was said that flagpole-like trunks of oak and maple surged out of control, like steam trains, in the muddy currents. Immense barges used the river as a superhighway moving coal, concrete and grain to the Gulf of Mexico or north to the headwaters of the Ohio River. The wake from their huge engines could topple boats – and would easily crush a lonely canoe. At this time of year, and with the river being in flood, it was a dangerous route to take, but one we took with clarity, caution, and commitment.

A month and 650 miles earlier we’d put in at the headwaters of the Little Tennessee River after crossing the Great Smoky Mountains on foot. It was here back in 1838 that the Cherokee were forcibly removed from their Tennessee Valley homelands as part of the Indian Removals, instigated by then president Andrew Jackson. As one of the five civilised tribes, the Cherokee were moved against their will by steamboat over 900 miles up the Tennessee River, down the Mississippi to Memphis, and onwards to the mouth of the Arkansas River. From there they were taken further upstream into Tahlequah, the modern-day capital of the Cherokee Nation. Over 2,300 Cherokee were sent in waves for months. Steamers towed flatboats loaded with families. Heavy rains soaked their clothes. Cold winds whipped off the water, and they survived on cornmeal, flour, and bacon grease.

It had taken us a month of paddling to follow the exact removal route and be within reach of Cairo (Kay-Ro), Kentucky. This busy barge harbour and fleet location is an infamous point where the Ohio River and the Mississippi converge. Due to high winds and conditions detrimental to paddling we’d found shelter in a dense oak treeline a few miles from Cairo. A mile downriver we could hear the hum of road traffic over a half-moon-shaped bridge made of rusted blue iron. To our west across the river we could make out white barges that sat motionless awaiting cargo, captains, and orders. Charcoal-grey clouds bubbled and rotated 1,000ft above them – thunderstorms in the making. It was 4.00pm and we had a decision to make. Stay here, let the winds and storm pass with the possibility of hunkering down overnight, or paddle hard for seven miles through potentially dangerous conditions to our intended stop at Wickliffe, Kentucky. The lure of shelter, coffee and warmth was almost as strong as the winds that would inevitably try to stop us.

Hugging the treeline was always our decision in poor weather. It offered protection and some measure of safety. As soon as we decided to leave the safety of the trees, committed paddles slipped into the water. Within minutes we weaved amongst the flooded treeline and worked our way down under the iron bridge. Passing underneath, paddles ceased to move as we watched the beautifully hypnotic architecture of the iron structure pass overhead. I was momentarily envious of the people in the security of their cars, no doubt sipping from ice-cold cups of water.

As we worked the calmer eastern currents on our way downriver, to our west the storm became ever more ominous, readying itself to be a late-afternoon showstopper. Its width and height grew, and it churned darker with every minute that passed. Looking over my right shoulder as we approached the convergence point of the Mississippi, I noticed the bridge I’d seen upstream slip away from view into a wall of solid grey. From long experience in this volatile region we knew this was a bad sign. Something was about to hit and hit hard.

During the previous hour we’d continued to hug the shoreline. Static shipping containers used by the barges for delivering resources sat along the flooded banks, side by side, like parked cars outside a sports stadium. For safety we would paddle the slow waters that flowed in a 6ft gap between the rusted barges and the lush green riverbank. Sometimes 100ft eddies would form between sets of containers, giving us time to survey the weather, eat, and rest. Sometimes we’d notice the current pick up and slide under the barges causing an uprush of waves. There was no rhyme or reason to which of these occurrences would occur and where.

As the storm began to approach and open up it was as if Mother Nature had decided to dim the lights. Orange turned to grey. Grey turned to black. Rain fell in waves as if directed from the devil himself. In this volatile weather region, unimaginably ferocious winds accompanied the violence of the thunderstorm. Shielding ourselves, we decided to stay behind the barges and slowly pick our way down the river using the 6ft channel. Emerging into a suspected eddy I spun the canoe sideways to view the hypnotic V shape of bubbling cloud formation above. I looked up. Its apex reached beyond the horizon into oblivion. In the rain Jamie unzipped his DSLR and began altering the settings to capture the dizzying array of natural forces.

It was here that I noticed our sliding sideways movement. We weren’t in a static eddy at all but a violent sweeping current. Glancing quickly left, the canoe began rotating, swept in the direction of one of three immense floating containers. Its rusted angular front was poised to crush and rotate us into its underbelly, drowning us both. I had 10 seconds to decide if we lived or died.

An instinctual shout of directions reached Jamie through the driving rain to the front of the canoe. Dropping the camera, he acted at once and paddled ferociously. In those seconds I’d turned the canoe to angle away from the approaching containers. With the power of forward motion, we would be away and hopefully around. Each moment seemingly dragged us closer to the mouth of the vortex that would inevitably pull us under the container. Paddles moved as fast as they’d ever moved. Words and instructions emanated from a primal and unconscious partition of my brain. At that moment everything was instinctual.

The commands of ‘Power! Power! Right paddle!’ brought us to the safer front-left edge of the container in seconds, where I put the canoe into a hard-left turn away from the violent current sliding under the barge. In those seconds the canoe was propelled forward at an unimaginable speed 5ft from, and parallel to, the container’s longest side. As I looked up, heart in mouth, I noticed a huge moving barge 20ft to our right, engines thrusting forward against the strong oncoming currents and wind, heading straight for us. This couldn’t be a more dangerous scenario. In seconds we were propelled through a narrow gap between the oncoming barge and the container, like water spat from a pinched hosepipe.

Within 10 minutes I’d pulled the canoe left into a small secluded cove behind a grass island and in front of a barge repair shop. Torrential rain was now filling the canoe. As I stared down at my worn, calloused hands, I realised that I was shaking. Jamie sat there in silence, head down. Even though it was raining and cold, the adrenaline muted our capacity to communicate. Laying the paddle across my lap, I managed, ‘Do you know how close we were to drowning there?’ There was silence, followed by a nervous laugh and a number of muffled expletives.

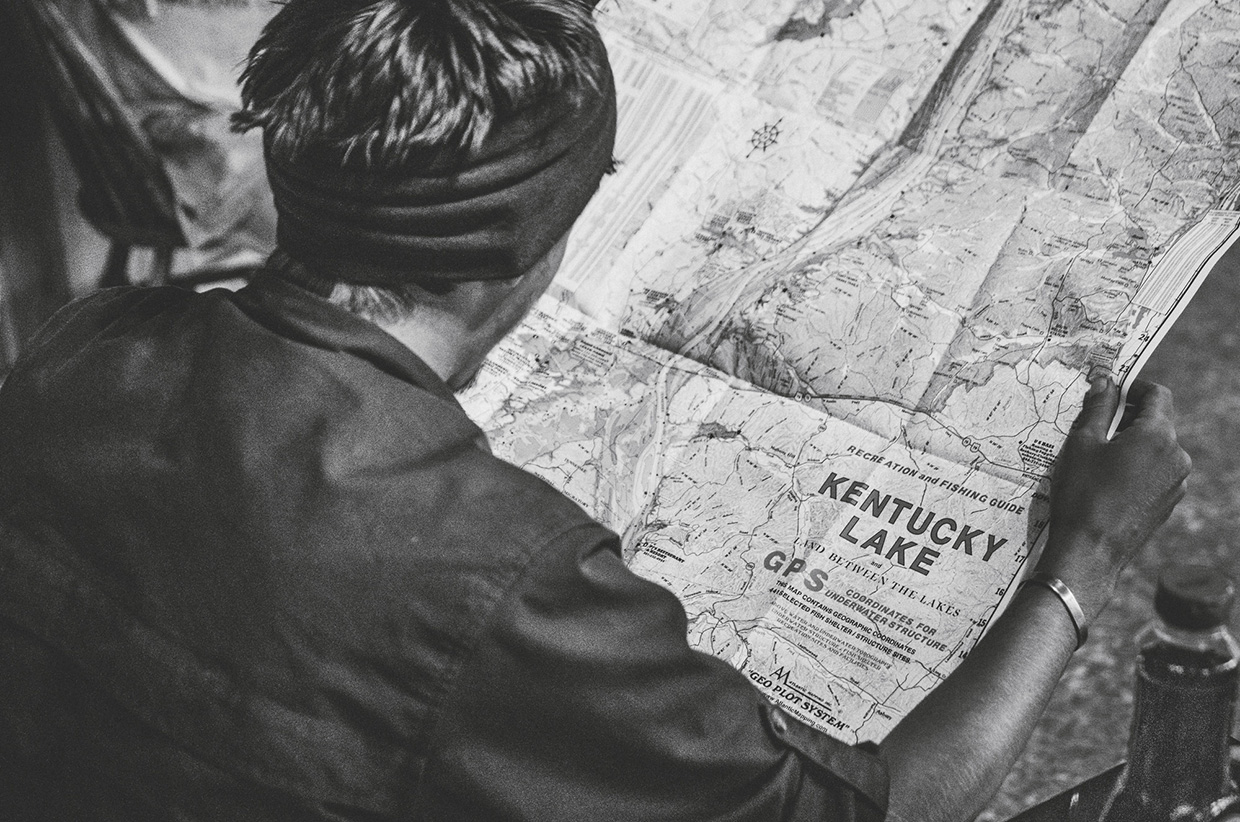

That night I couldn’t sleep. Every time I closed my eyes I would see red – or was it purple? I would see the barge and the violent sideways water sliding under its nose. I would see snapshots and evaluate my decisions. I would remember people telling me after the event that large boats and even whole barges had been crushed in the front-end vortexes, like Coke cans through a crushing machine. Later, after surveying detailed maps, we would find out that the flooded Mississippi and Ohio rivers converged exactly at that location – the start of a large sweeping right turn, a river’s fastest and most powerful point. We later learned that the fact that the Mississippi was flooded at that spot had nearly doubled the speed of its already strong current.

Two weeks later, we grounded the canoe for the final time in Memphis, Tennessee.

We’d paddled 900 miles in flooded conditions and completed a large portion of the original removal route made by the Cherokee during the removals of 1838. From this modern metropolis we would take stock of our journey and what we had learned about the Cherokee’s fight for survival during this catastrophic time in their history. From Memphis we would regroup, repack kit, and send supplies home. We would also look ahead to following the final 440-mile route the Cherokee took across Arkansas on foot, ending in Tahlequah, Oklahoma.

The last time we saw Sequoyah, our workhorse canoe, she lay listed to one side in a workshop next to an old run-down Jaguar and a 1960s pleasure boat. Above it hung more canoes and remnants of other journeys along the Mississippi River, mementos in their own right.

I thought it funny that nobody had any clue what she, or we, had endured.

To be continued.

Ian Finch and Jamie Barnes are currently on a 1,200-mile journey to retrace the steps of the Cherokee. We’ll continue to post updates from Ian and Jamie here and follow the journey via our Instagram story updates.

Words: @IanEFinch // With @JamieBarnesUK