Finding Magic In Alaska

Dave Gill

Back in late 2012 I’d set off to cycle around the US and Canada; eight months later I was in Alaska, walking along the Stampede Trail, just outside Denali National Park. The location of ‘the magic bus’. The place that Christopher McCandless used as a base to live off the land, and the place where it’s believed he starved to death. 20 miles away from the nearest town, away from people, with just moose, grizzly bears, 2 river crossings and a whole lot of Alaskan greenery for company.

For eight months cycling had been my life but now needed a break. In all honesty, it was driving me crazy. So much was going through my head that I was finding it hard to keep it together. Despite some incredible highs, I’d be lying if I said there hadn’t been some serious lows too. Mainly it was because I was doing the same thing for so long alone. I was wondering why I was doing it and why I wasn’t sharing the experience with someone else. Wondering whether I was a selfish person and whether there was something wrong with me for being drawn to these kind of trips. There had been lows recently that I’m not proud of. Some involving stopping, letting the bike fall over, and screaming out ‘FUUUUCCCCKKKKKKK’, head in hands and taking a moment – or two.

I needed to do something, anything that didn’t involve the bike. So I stopped pedalling when I reached a suitable building in Fairbanks and, in a typical Brit-on-an-adventure fashion, heightened my British accent to charm the receptionists with memories of Colin Frissell from Love Actually, and asked for a favour. Hopefully they’d be oblivious to the dirtiness that had built up recently. Thankfully they were, or at least didn’t mention it, and said I could lock up my bike and gear behind the building, and agreed to look after my electronics in their safe. Colin’s accent worked. It works a lot in the US. Thanks Colin.

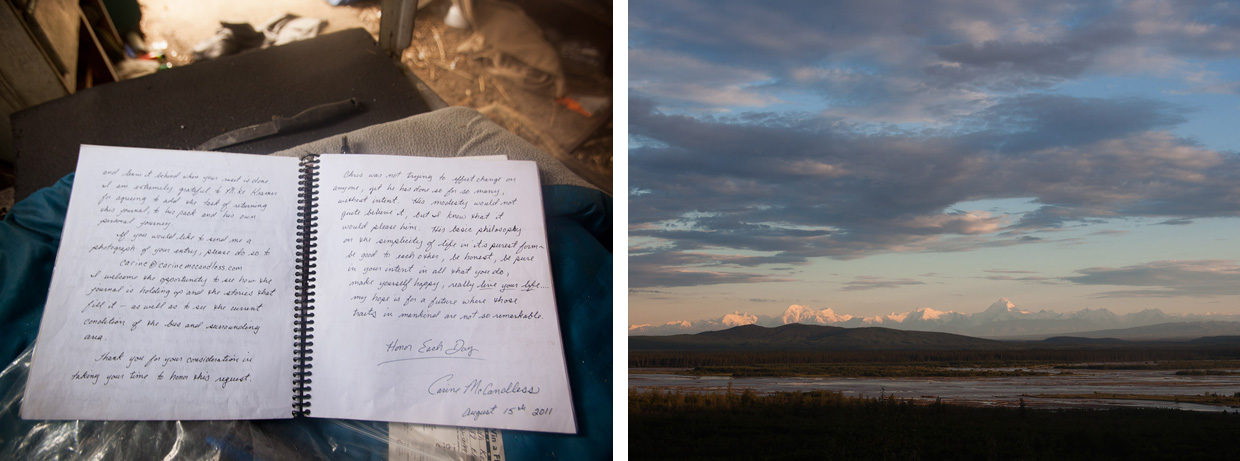

I recall reading Into The Wild as an 18 year old. It’s a divisive story and touching in many ways. McCandless was willing to forgo obvious security to be drawn to a life of adventure, a desire to question perceived normality and a search for simplicity, solitude and self-sufficiency. That’s something not many people do when we’ve never been so busy, on our phones and constantly hitting the 9-5. Throughout the Alaskan portion of my adventure, I’d be reminded of the distaste the locals had for McCandless and his story. Exactly the same distaste I have for tourists who arrive in the Lake District and get lost or sprain an ankle and call for a helicopter rescue. Alaskans think of a disillusioned dreamer, naive to the realities of surviving in a harsh environment. They hate that people come from around the globe and get themselves in trouble, some have even been killed, after being spurred on more often than not by Sean Penn’s Hollywood adaptation.

A break was necessary, for sanity if nothing else, and I was in the area, so the decision was made. I didn’t expect it to be a profound experience or anything, and honestly, looked at it as more of a nice two day walking holiday than a spiritual pilgrimage. I went to the supermarket in Fairbanks just before it closed, bought a pack of 24 granola bars, and set off with a camera bag acting as a walking pack, a small tent, no sleeping bag, minimal running shoes and a 5mm thin foam mat – light and fast. Plus because this was a cycling trip I didn’t have access to walking gear.

So much was going through my head that I was finding it hard to keep it together. Despite some incredible highs, I’d be lying if I said there hadn’t been some serious lows too. Mainly it was because I was doing the same thing for so long alone.

The Tek demonstrated its power. I didn’t expect the strength of the torrent. I was halfway across the river and twice, my right foot was pushed violently downstream, causing hairy imbalanced moments. Staying upright all came down to that thick stick. Halfway across, and the river was presenting itself as the danger that it is.

A few miles in to the 40 mile round trip now. The mosquitos. I hadn’t been expecting them. They hadn’t posed a problem anywhere except here. But it was bearable, a rapidly reducing tube of deet provided solace. The issue on the way in to the bus wasn’t a physical one. It was mental. HUMAN. That word. People say to stick to a single keyword, and in bear country you call it out, the theory being that bears are more scared of humans than we are of them. HUMAN. 30 seconds. HUMAN. 30 seconds. HUMAN. It’s a unique monotony that will drive anyone around the bend.

I was at the major river crossing now. It’s known as the Tek. It’s personified by its reputation. The Teklanika River. This was a significant point of no return for McCandless. He crossed it when it was low, in late April 1992. When he tried to walk out three months later, in July, it was too high so he returned back to the bus and died. That all happened on the other side of the river to where I was now stood, maybe 40 metres away. I’d half-expected to turn around here. Sometimes I think we actually want these kind of obstacles to present themselves, because it makes decisions of retreat far easier. I half-wanted the river to seem scary and intimidating. But it didn’t look that bad.

Find a thick stick; put it in front of you; feet wide and face upstream was the trick. Become a human tripod and shuffle across the river. Always prepared to ditch your rucksack and swim if needed. Downstream from the crossing is dangerous, so you must get out fast. I’d read the river reports and the hype that this stretch of water has in July. But the shuffle seemed to be working.

Then the Tek demonstrated its power. I didn’t expect the strength of the torrent. I was halfway across the river and twice, my right foot was pushed violently downstream, causing hairy imbalanced moments. Staying upright all came down to that thick stick. Halfway across, and the river was presenting itself as the danger that it is. Upon reaching halfway, the focus you have on the opposite river bank makes up your mind for you. I kept going, and a minute later took a breath and realised that there was more luck involved in staying upright than I would care to admit.

I sat down on the far bank and looked back across the Tek, my mind forming a picture of what the circumstances may have been like on that day in 1992. Starving, ill, tired, weak. Those are things that would make any person looking at this crossing feel an overwhelming sense of terror and isolation. The next few hours on the trail were mainly spent in tree lined corridors and walking up dry, rocky riverbeds. In those moments, it was a type of walk that wouldn’t be at the top of a list for quality. But sometimes those trees and riverbeds ceased and the beauty of the area presented itself. It was magical. Open tundra, with colourful plant life, birds flying high and a magnificent mountain range as a backdrop.

And then, as the trail opened a little, there it was. It was like walking in to a natural courtyard –the 142 bus nestled at the back. It was quite an eerie experience. I was happy to be here, at the destination that I’d set for myself, a mini-goal accomplished. Yet the backstory and what happened here niggled at the back of my mind. It’s been many years now of course, and has seen lots of traffic. It shows too; the bus has been vandalised, bullet holes in the exterior, windows broken and much of its innards stolen. But there’s also signs of hospitality here. There’s emergency food and blankets and a visitor book. It has a foreword by Christopher’s sister Carine and is brimming with tales from those who have made it here. From Japan to Nebraska, England to Egypt. The magic bus seems like a place that people are drawn to when they want to get away from it all and live simply for a while.

I camped outside the bus, on edge most of the night and sporadically shouting HUMAN, except for when my body took over and I couldn’t stay awake any longer. Hours later I woke to a sun a little higher in the sky, pounding down on the tent’s shell, raising the temperature inside rapidly. It’s the earth’s way of telling you it’s a new day. And all that was left to do was to have another granola bar, squeeze all remaining droplets of deet from the tube and turn around, hoping the Tek hadn’t suddenly risen and all the mosquitos had left in the night. Thankfully the river was fine, but the little terrors remained.

After returning to Fairbanks, I spent the next three days limping, blistered, itching and barely able to move. Although I was over the moon to not have to shout HUMAN again, I knew it had been worthwhile and for one reason. Sometimes retrospect can be a confusing mistress, as now the thought of being eaten alive and going loopy in Alaska doesn’t sound so bad. But this time, it wouldn’t be an individual pursuit. Regardless of what you think about McCandless and his story, in his last moments, he wrote in his journal ‘Happiness only real when shared’. A very important message for all of us.

Dave Gill is a filmmaker and writer from the Lake District. He recently spent a year cycling around North America, meeting a diverse range of people to talk to them about the lifestyle choices they’ve made.

Website: www.vaguedirection.com

Twitter: @dave_steepmedia

Facebook: www.facebook.com/vaguedirection