Pull of the North

Journey's End

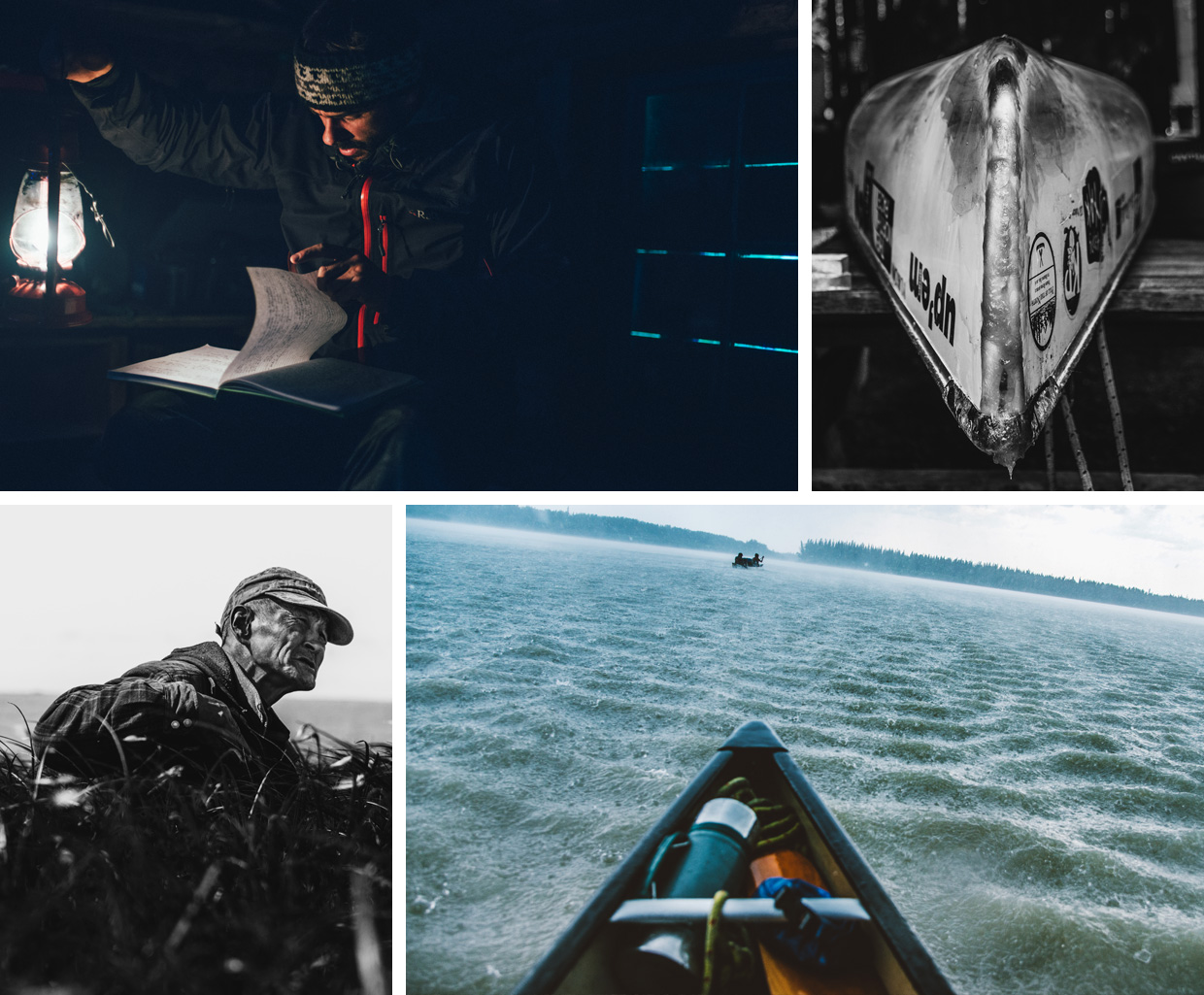

Ian Finch // Photography by Jay Kolsch

In Sidetracked Volume Eight Ian Finch tells the story of enduring torrid days with the paddle, negotiating the Yukon River’s furious whitewater to study the region’s remaining native cultures. Ian continues the story here, focusing on the end this immense expedition and the impact that it has had on his life.

Just off-shore, our battered canoe jerked from side to side in the afternoon swell. 68 days of dry mud sat cracked and flaking under my feet. Although the four of us had paddled every day together, both canoes now fell silent. Our vibrant smiles might have lit up the sky. I gripped the paddle more tightly, rotating it, readying it, hands wet and even a little cold. Yet warmth came from a flush of joy, the feeling of imminent closure that comes at the end of a major challenge. It came from the charge of electricity surging through me as the realisation of our success grew goose bumps on my skin, like the birth of some tiny mountain range. There was only sixty feet of water left until the end of our expedition.

“It wasn’t, of course, the beginning, for who can say where a voyage starts – not the actual passage but the dream of a journey and its urge to find a way.” – River Horse, by William Least Heat-Moon

Nearly two years ago, I stood in front of the world river map that hung in my apartment in North London. My eyes scanned continents, countries, and provinces for the perfect arterial candidate. Highlighted in blue, I traced the rivers with my fingertips. I visualised the twists, valleys, and portages. A year before that, I had been on expedition in Greenland with Inuit hunters and now I was being enticed back towards a different native group: The Athabascans of Canada and Yup’ik of Alaska.

From a young age, I’d been fascinated by indigenous people. I would sit in the back room of my parent’s house and leaf through the dusty pages of my father’s books on Native American history. Their old, sepia photographs would seize my imagination and captivate me. The poorly-translated passages from tribal languages would resonate within me, carried along by a thirst for understanding. I would fill in gaps as to how I envisioned their lives to be. As a grown man, some years later, I would soon look back and learn that this childlike yet intuitive urge was the smouldering ember of curiosity waiting to be fanned into the flames of a life spent in cultural exploration.

Although the four of us had paddled every day together, both canoes now fell silent. Our vibrant smiles might have lit up the sky. I gripped the paddle more tightly, rotating it, readying it, hands wet and even a little cold. Yet warmth came from a flush of joy, the feeling of imminent closure that comes at the end of a major challenge.

Having now returned home, the impact of the Yukon and its people has gone well beyond the metaphysical. My mind has become a storm of new expedition ideas. My heart pines for the wilderness I have left behind. Meeting such a rich and diverse culture has clawed deep into my psyche and ripped up the script to my modern existence.

Having now returned home, the impact of the Yukon and its people has gone well beyond the metaphysical. My mind has become a storm of new expedition ideas. My heart pines for the wilderness I have left behind. Meeting such a rich and diverse culture has clawed deep into my psyche and ripped up the script to my modern existence. Making sense of what I’ve learned has become a daily retrospective: going past the physical aspects of the journey and looking deeply inwards towards to the spiritual. Evidently, what happened out there irreversibly changed my blueprint and structure forever.

The people of this vast river system live within a simple framework of ancestral beliefs and ethics. Even after 10,000 years, the cyclical nature of the seasons still govern their way of life. Each season brings both natural challenges and things to be treasured. Animals are killed for food according to ancient rituals and at specific times of year. In some cases, the blooming of a flower, or the sight of its seeds carried along on the breeze, foreshadow the coming of an animal ready for harvest. These peopled don’t use the word ‘hunting’, instead they say ‘harvest’. They believe an animal gives itself up for harvest at certain times of the year, like the cycle of crops within the seasons. Communal rights are based on a belief that the natural and the spiritual worlds are as one, and respect for the land is not only deeply rooted in their physiology, but is a religious duty passed down orally from their ancestors. For these people and their families, the perpetuation of their culture, language, and belief system is as important as the rising and setting of the sun.

However, for cultures in this region, modern life is not easy and survival is hard. With the dark and conflicting touch of modernity reaching many of these small villages, the ancient ways are under threat. Daily life has become a constant balancing act between the modern and the traditional. As small community stores open offering quick-fix food, alcohol, and other modern conveniences, the necessity to live from the land depletes with every passing day. In a place where the bond with both the wildlife and the landscape it inhabits offers a strong, ancestral resonance, breaking that bond would be catastrophic for the people and their future. With the help of community elders, tribal officials, writers, and oral dictation there is a positive push back taking place in every home and village. This fight is to preserve an ancient way of life and the memory of their ancestors. This fight is to inspire the next generation and save a culture.

In a final conversation with an elder I was told: ‘For the people of this region, night and day, sun and moon, sky and forest are all hours and are seen as a breath in our human spirit.’ Within this cultural and spiritual insight, and many others like it, I found the simplistic beauty of life I’d be looking for all along the river. I’d also found a culture so rich and connected to its surroundings it was as if those ancestral veins that permeated each tribal family could actually be held in my inexperienced hands.

I realise now that in my quest for knowledge and understanding on this expedition, I was subconsciously in search of a set of beliefs with which to govern my own life. Somewhere deep inside, between the vibrating structures of my own cells, I yearned for the simplicity of their wilderness existence, with all its stresses and struggles combined. I also craved a connection to something older, greater, and more alive than the pursuit of a modern career or social standard. Being connected to the landscape, their way of life and understanding the complex nature of the wilderness world around me is now as important to me as the rising and setting of the sun is to them. It was there, amongst the people of the Yukon, that I finally found a true reflection of my spiritual self.

We had discussed delaying that final moment, when the canoes pulled in for the last time and the expedition was at an end. Our plan had been to permanently memorialise the sound of the canoes making land one last time. For each of us it would be a final and enduring audio reminder of the Pull of the North. In the end none of that seemed necessary. What we had learned was in our hearts already. As the canoes drifted into the coastal fishing community of Emmonak, Alaska, we did what we’d always done: hugged, smiled, and discussed where we would sleep that night. Later, standing in the silky mud, I watched as my canoe lay lifeless in the water. I took one last mental snapshot of her in this state, packed up and ready for another river, hopefully somewhere remote, and treasured that instead. In an hour or so, she would be an empty carcass, adopted by a tribal family and listed to one side on this mud bank. No longer mine. Tapping the plastic gunnels with my palm I walked away pulling my heavy green rucksack onto my back. Beneath the peak of my cap, as the sun set, I looked back over my shoulder. There’s nothing more beautiful than one last look.

Read Pull Of The North, the story from mid point in this expedition, in Sidetracked Volume Eight

Ian Finch is a cultural researcher who’s been passionately travelling to remote environments to learn about 1st nations communities for over 4 years. His endeavours are regularly filmed and shared in an attempt to inspire and educate about people in far away regions.

Website: ianefinch.com

Twitter: @Ian_efinch

Instagram: @ianefinch

Facebook: /Ianefinch

You’re more likely to run into Jay at an airport than in his neighbourhood in Brooklyn. As a full-time adventure photographer he is constantly on the move seeking the unexpected in far off places. He feels most at peace when exhausted, dirty and far from home.

Website: jaykolsch.com/

Tumblr: jaykolsch.tumblr.com/

Instagram: @jaykolsh

Facebook: /jason.kolsch