Returning to the Ice

From The Field

In Conversation with PrimaLoft Ambassador Lonnie Dupre

Written by Alex Roddie // Photography by Lonnie Dupre and Eva Capozzola

Produced in Partnership with PrimaLoft

‘You’ve got to be travelling in tune with the environment, not fighting it.’

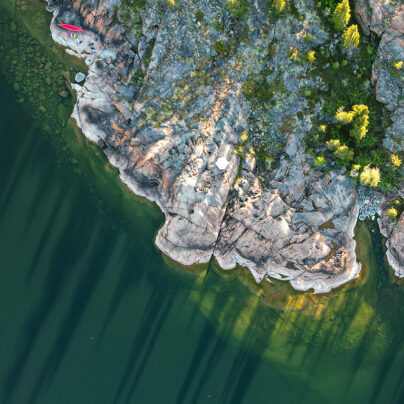

In 2001, explorers Lonnie Dupre and John Hoelscher completed the first circumnavigation of Greenland – a multi-year 5,000-mile journey by kayak and dog team. In 2022, Lonnie returned to Greenland, accompanied by adventure photographer Eva Capozzola and Polar Inuit hunters Sofus and Qajorannguaq Aletaq. Our editor Alex Roddie caught up with Lonnie at Kendal Mountain Festival, to chat about returning to visit old friends, as well as witnessing vast change to both culture and environment.

Alex Roddie: What motivated you to attempt the first circumnavigation of Greenland in the late 1990s?

Lonnie Dupre: One of my motivations was to learn about Greenland, and the best way to learn about it is to go all the way around, right? And do it by ski or dog team in a slow manner, not by vehicle.

The circumnavigation of Greenland had never been done before, because it’s massive. The east and west coasts are choked with sea ice, so you have to be amphibious, you have to be creative. You also have to be safe because capsizing and getting hypothermia is a real threat.

We were lucky to be able to complete the entire expedition without any major snafus. We diverted a few big ones that could have ended the project. But I think that just made me love Greenland even more, having spent so much time there.

Immersion is a word I noticed in the film. You’re immersing yourself in the place rather than going with a goal-driven objective at the front of your mind.

You’ve got to be travelling in tune with the environment, not fighting it – which is unfortunately what a lot of expeditions are doing. When the weather or water stops them, they’re disappointed. But that’s not what we’re there for. If the weather is bad, we stop and wait until it’s better. We don’t push.

The Greenland dogs are central both to your experience of Arctic travel and everyday life for the Inuit. In the film, there’s a memorable line: ‘Through the dogs you experience the wilderness.’ Can you expand upon this?

They emit this sense of adventure – a sense of wild. All the successful expeditions from the age of exploration – Peary, Amundsen, Nansen – were successful because of those dogs. Without them they wouldn’t have made it. So naturally I’m drawn to that spirit and companionship. The dogs will protect you with their life and we will do the same for them.

The Inuit could not survive without them. They use dogs for travel, for hunting. The dogs can surround polar bears and chase them out of camp. They can also smell where a seal breathing hole is, and seals are bread and butter for the Inuit!

You can have a relationship with a dog, but you can’t have a relationship with a snow machine. Snow machines break down. They take a lot of fuel, they’re expensive, and they scare the wildlife you’re trying to hunt. Dogs are silent, reliable, and start in the morning!

Dogs are a lot of work, no question, but that work pays off tenfold.

The film describes Greenland as an enclave of traditional culture. Why do you think many of the Inuit have held onto this traditional way of life?

Indigenous cultures adapt to the environment, and they’re very good at improvising and making do with what they have. Meanwhile goods from beyond Greenland are expensive. Their traditional ways are often better, simpler, and cheaper.

What I’ve learnt most about them is seeing how these people do so well in such a harsh environment with so few material things. We can all learn from that, can’t we?

How did it feel to return to Greenland and travel with dogs for the first time in so long? What drove you to go back?

My real love is travelling by dog. On our circumnavigation we spent about 3,000 miles running with dogs. So after being gone for over 20 years, I wanted to go back mainly for the dogs again – but also to visit friends I’d taken photographs of decades ago, and finally to see how climate change and their culture have evolved in two decades.

The first thing I did was gather up a dog team. I purchased 14 Inuit dogs. I had my own sled shipped up there, which I’d learnt to build from them years ago.

Organising a team, helping them get along together, letting the dogs know they can trust me, and then travelling with those dogs… it’s like being on a magic carpet being pulled through clouds. That’s everything to me right there. I could do that for the rest of my life and not do anything else.

What changes did you witness in the culture?

When we first went to Greenland, they’d just got a black and white television for the whole village, and they were watching a sitcom from Denmark. They were all still dressed in furs and had a 2,000lb dead walrus they’d dragged in from the sea ice, and were all sitting around watching this sitcom. There was one radio in the whole village.

Fast forward, now you’ve got Facebook, satellite communication, all the things. The old ways and new ways aren’t blending very well. Now everyone’s spending more time on their phones, less time out hunting. Like for us here, the phones are an addiction – we’re all in the same boat. Instead of being out on the land, they’re looking at things on their phones that are simply unobtainable in Greenland. That’s the difference.

It’s such a huge disconnect and it leaves a lot of the younger generation questioning their meaning in life. Any time the Indigenous youth try to go to Denmark to get an education, they get extremely homesick because they grew up in a village where they know every centimetre.

It’s hard to take a people who have been hunter-gatherers for so long and then transform their way of life so utterly in two generations. A far more rapid pace of change than most Western nations went through during industrialisation. We haven’t coped with it very well ourselves, so why should they?

And the environment – what kind of change did you see there?

The coastlines have been so distorted over the last 20 years, with glaciers melting away from the coast and exposing new contours, that the Danish government is making new maps of the entire coastline. When you’ve got to make new maps you know you’ve got issues.

The sea ice loss is devastating for the Inuit because there’s no road network. The only way to get around is by sea ice. If that ice is gone, you’re landlocked in these communities that already have issues, and depression is going to go off the charts. Their cure for depression is to get out and run with their dogs. They’ve got some tough adaptations to make in the coming decades.

One thing that really struck me is that you’ve been talking to audiences about climate change in the Arctic for a lot longer than most other speakers – well over 20 years. How does it feel when you look at the world’s response?

Nothing’s sunk in. Our elected officials have failed us colossally. We can put the blame directly on them. They try to put the blame on us, but no-one’s given us other tools to work from.

When people ask for solutions, I say that driving an EV or switching to paper straws aren’t bad things to do, but they’re not going to pull us out of our dilemma. The only thing that’s going to do that is environmental legislation on a humongous level in all the major countries.

I want to give younger generations hope, but I’m finding it really hard, other than telling them that they need to stay politically active and vote for somebody who cares about the environment. Also, we can’t stop what’s coming down the pipe. So you need to prepare for it. You need to adapt. I want to be truthful, and it’s a little sobering, but we need to be realistic.

And that brings me to the next point, which is the role of adventure and exploration. People such as yourself change minds. But I think everyone here at Kendal cares about the environment. Do you think adventure and exploration is changing enough minds, and quickly enough? How can this whole community do better? Is what we’re doing effective?

That’s a big no. Right now, we have enough research; we lack solutions. What we need to do is say, ‘Hey, we know climate change is real. How do we solve it?’

We need solutions-based expeditions. Have a campaign to plant some trees, for instance. Encourage political activism. Concrete solutions! Good examples include the avenues that companies like PrimaLoft and Patagonia are taking right now. Patagonia, for instance, is a leader, taking 1% of their profits and giving it to environmental causes.

Do you think enough brands are doing that? Have you seen enough progress in the outdoor industry?

It’s slow but coming. And people are understanding that brands can’t just produce a product and not give anything back. You can do it through clothing that’s well made, so you don’t have to buy again down the road, or it can be biodegradable, like PrimaLoft’s doing.

The consumer picks up on that. When people buy Patagonia or PrimaLoft, they feel good. It’s going to take a lot of companies a long time to get there, but I think we’re making baby steps.

And can you share anything about solutions-based expeditions you’re involved in?

We’re launching an expedition called Nord Hus, a sailing expedition from Minnesota, wiggling an Arctic vessel through the Great Lakes and down the St. Lawrence Seaway, out to Labrador and Newfoundland, then across to Greenland. We’ll have a scientist from Adventure Scientists joining us, and will combine a solutions-based effort. That might mean promoting the planting of trees or some other concrete solution, but we’re still dialling that in at the moment.

Do you think that adventure for adventure’s sake can still be justified given the challenges the world is facing? Rather than making a pretext for it, should adventurers sometimes just say, ‘You know what? I just want to go and have an adventure!’

Absolutely! In between our big adventures we do lots of smaller ones. We’ll go canoeing across the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, ice climbing somewhere. I do this because it’s been part of my life for 30 years. But I do think bigger expeditions should be justified with a genuinely good cause.

These adventures in the middle can keep the passion burning. And in my case, I’m getting older now, and sometimes it’s just to stay in shape and be around friends. There’s always going to be value in that.

Produced in partnership with PrimaLoft.

Amka, a film by Eva Capozzola about Lonnie Dupre’s return to Greenland, premiered on Friday November 22nd, 2024, at the Kendal Mountain Festival.

Read ‘Qimmiq’, the story of Lonnie Dupre’s 2022 expedition, in Sidetracked Volume 29 or online here: sidetracked.com/qimmiq

Written by Alex Roddie // @alex_roddie // alexroddie.com

Featuring Lonnie Dupre // @lonniedupre // lonniedupre.com

Photography by Eva Capozzola // @evazolaphoto // evazolaphoto.com

In partnership with PrimaLoft // !primaloft // primaloft.com