The Last Slice

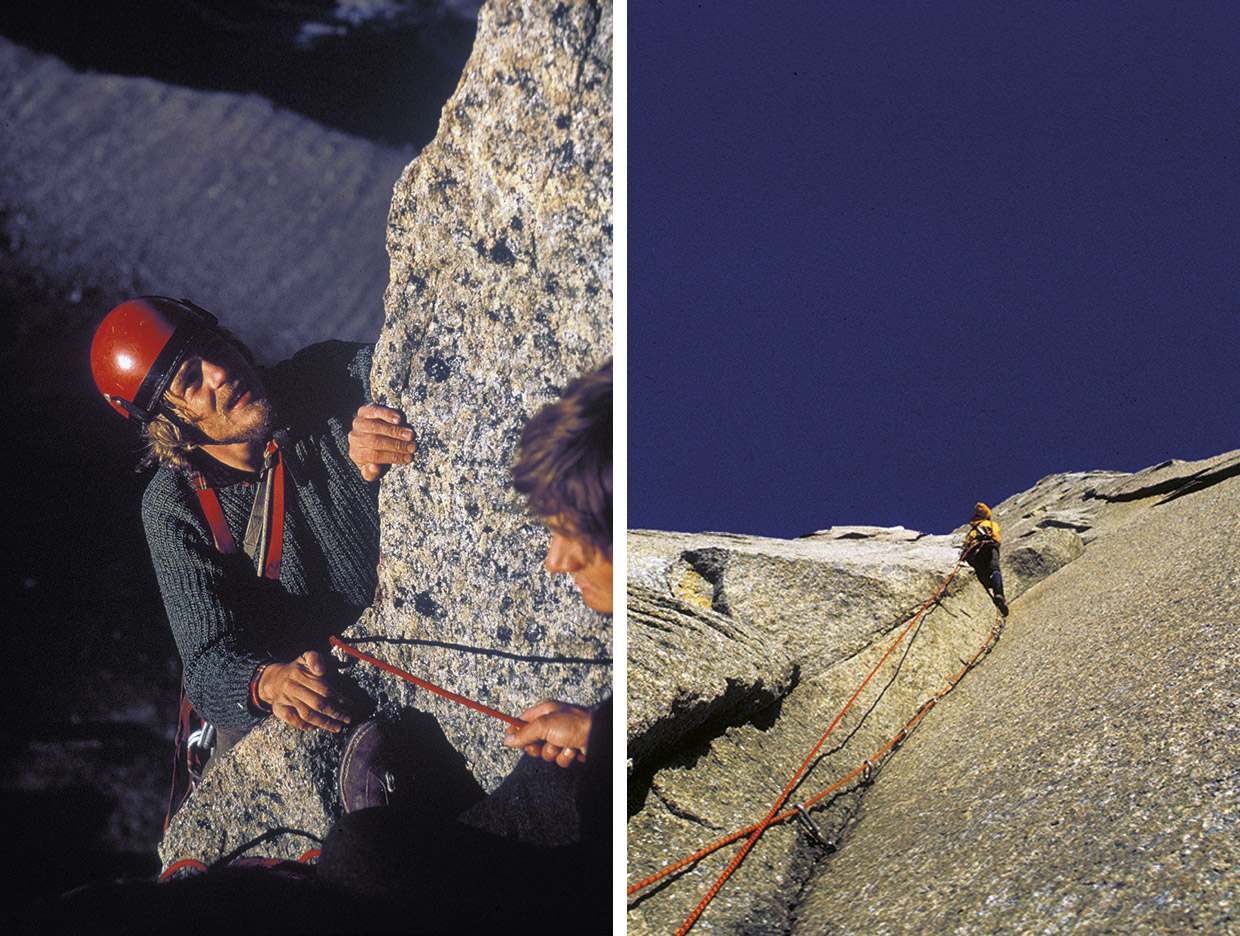

Exploring Baffin Island (1971)

Doug Scott

After two weeks, a patch of blue sky appeared through the swirling morning mist. By the afternoon the sun was out and we were being bitten by a thousand ravenous mosquitoes. Given the loss of time, we decided to concentrate on two big walls near camp. So far, exploration on Baffin, such as it was, had focused on exploring and making first ascents by easy routes. We now hoped to do something never before attempted in Arctic Canada and climb one of the big granite faces around us. Guy and Phil set off that same afternoon for the elegant 2,000-foot north buttress of Breidablik.

The rest of us also took advantage of this respite from the weather. The east face of Freya Peak reared up for 3,000 feet in slabs and a headwall to a point easily seen from our camp. We named the point Killabuk, since the main summit of Freya was set well back towards Asgard. We regretted not making an earlier start since the slabs were at 5.7 a bit harder than expected and required a rope. The headwall was also more difficult than we bargained and with very little food and no bivvy gear we debated whether it would be prudent to retreat. We sat around undecided until Dennis said, ‘Well, why don’t we just go up and have ourselves an adventure.’ As one came the reply: ‘Yeah!’ And so we went for it.

Towards evening we were on the headwall but the crack system we were following ended abruptly. We could neither free climb nor peg our way up and so the only solution was to arrange a pendulum and try to reach another line of cracks away to the right across a hundred feet of blank rock dripping with water. From a peg placed as high as possible we fixed a rope and slid 150 feet down it. One after the other we swung backwards and forwards, gathering momentum and distance until we could clamber into the new crack. After this exhilarating manoeuvre we made good progress to a ledge suitable for a miserably cold, wet bivouac. Winter was obviously drawing nearer for there were now a few hours of dark. We were only 600 feet from the top but the headwall overhung its base by fifty feet and we found the climbing strenuous.

Next morning, as the crack we had gained was now overhanging and full of loose flakes, we followed a ramp round to yet another crack system, crawling along as the ramp narrowed alarmingly. Right at the end it was just possible to stand precariously in balance and reach for a ledge. I tried not to notice the thousand-foot void below. From the ledge I stepped round a corner into sunlight as the sun rose, each of us warming our cold bodies and numb fingers as we flopped down on a large ledge.

Above, the mountain was cleft by chimneys set at right angles to one another. We wriggled and pushed, getting good friction from the rough red rock. Shafts of sunlight pierced the dark recesses of the mountain now full of the sound of heavy breathing and clanking pegs. After 200 feet we were disgorged on to a wide terrace below the final wall. In two more pitches of hard pegging and pleasant free climbing we arrived on the summit twenty hours after leaving camp.

We felt elated to be there, looking down on our tents and across at the peaks stretching out in all directions, still covered in fresh snow from the storms. It is always a good feeling to arrive on the top of an unclimbed summit. We lay out in the sun among the weathered rocks scattered about the flat summit. I took photographs of Steve venturing out on a block of granite jutting out for twenty feet above the slabs 1,200 feet below. Having been cooped up for so long in the tents we were doubly elated at having carved out a fine route involving a variety of problems and difficult route finding.

I tried not to notice the thousand-foot void below. From the ledge I stepped round a corner into sunlight as the sun rose, each of us warming our cold bodies and numb fingers as we flopped down on a large ledge.

Hurrying down the back of the mountain, we made six long abseils to eventually reach the Caribou Glacier. We arrived back at Base Camp a few hours before Guy and Phil. They came steaming in from their long walk home from Breidablik and quietly described the great climbing they had found and how, after eighteen long pitches of pegging and hard free climbing, with a bivouac in hammocks, they had reached the summit. Over the next few days Guy, Phil and Steve climbed a prominent unclimbed peak beyond Breidablik but the weather was bad and Mick, still gathering material for his film, was lucky to find a window in the cloud just as their three bright red anoraks arrived at the summit. To make sure we had a film of a climb in the can, Rob, Dennis and myself repeated Guy and Phil’s excellent route on Breidablik while Mick filmed us.

The wind blew in gusts of over a hundred miles per hour and pummelled our tunnel tent violently. It was a daft place to be testing a prototype but fortunately it survived. Wind whistled through the external poles like a flute while ice hammered into the tent walls with the sound of cymbals being brushed, reaching a crescendo.

We had ten days left. Having climbed eight peaks, including the rock faces of Killabuk and Breidablik, and having the film in the can, we could be reasonably contented the expedition had been a success and our sponsors would be satisfied. Yet at a personal level we were far from satisfied and never would be until we had climbed Asgard. The peak has twin summits, north and south. The Swiss team had climbed to the north summit in 1953 from the relatively easy east side, as reported in Mountain World. Guy, Phil and Rob now set off to climb the south summit by its south ridge. Dennis and I had walked right round Asgard a few weeks earlier with the ‘film crew’ helping carry 300 pounds of equipment. We considered climbing the west face of the south peak but eventually settled for a sweeping 2,000-foot dihedral on the north peak. To reach it we would have to negotiate a thousand feet of easier-angled mixed ground.

For a second time we moved into our lonely tent pitched on the glacier below the west face. The day after our arrival was overcast and cold but we went up to the foot of the dihedral and stashed all the heavy gear and food. We returned to the tent after ten hours’ climbing to await a settled period of good weather for our ascent which we thought could take up to seven days. During the night bad weather blew in and the temperature dropped to -10° Celsius. Snow piled up against the tent and we settled in to sit out yet another storm.

The wind blew in gusts of over a hundred miles per hour and pummelled our tunnel tent violently. It was a daft place to be testing a prototype but fortunately it survived. Wind whistled through the external poles like a flute while ice hammered into the tent walls with the sound of cymbals being brushed, reaching a crescendo. Every so often the end wall of the tent boomed loudly like a huge drum. Then it would be dead calm and we would wait, tensed, for the wind to come whistling back and slam into the tent, which flexed and shuddered at the new onslaught.

It felt good to be so close to the harsh environment lying in warm sleeping bags, a private world seven feet long and four feet wide where everything was orange. It played strange tricks on the eyes when we looked outside; Asgard had a blue haze, a cold Arctic blue, and was plastered in snow. With frozen water beneath us and frozen water masking our mountain, we talked of California’s sun-soaked mountains and surfing off Ventura. The only liquid in this frozen land was produced on our stove with its little ring of flame.

We slept, re-read Hermann Hesse and slept again. Still the storm continued. One morning a shaft of sunlight broke through and lit up the notch below the south ridge of Asgard and then reached the tent. The snow around us sparkled like a million diamonds until the wild grey sky closed in. We had managed to curb our frustrations up to now but we both knew time was running out and winter might have arrived. It had never been so cold. We packed up and, shouldering huge loads, walked out to the big tent at Summit Lake where we devoured a large quantity of chocolate bars from the mountain of food remaining. We sat around playing over and again Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young’s 1971 live album 4 Way Street and in particular Graham Nash’s classic ‘Teach Your Children’. We also wore out a copy of Bob Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home and its brilliant questioning of society’s loss of direction; the line about the president of the US sometimes having to stand naked was particularly relevant as Richard Nixon’s chickens came home to roost.

Climbing had started off so well but seemed to be turning out all wrong, as Melanie Safka sang in ‘Look What They’ve Done To My Song’. Dylan’s album was really an indictment of unbridled capitalism and consumerism; to me Dylan is a genius and a prophet without preaching.

Phil, Rob and Guy had gone around to King’s Parade Glacier on the east side and climbed the south ridge to the unclimbed South Peak of Asgard. The front that scuppered our attempt on the west face of North Peak caught them on the summit after twelve pitches of superb free climbing and just a little easy aid. The descent became an epic as light snow flurries turned into a full-blown blizzard. They were lucky to get off the mountain without frostbite. We both felt a little left out of this success but admired their effort. Climbing Asgard had added considerably to the success of the expedition as a whole.

We prepared to strike camp and walk out but faced with our mountain of filming equipment and camping gear, Rob, Ray and I volunteered to run the fifty miles back to Pangnirtung. The helicopter was still based there for another two days and we decided to hire it rather than make several journeys up and down Weasel Valley ferrying kit. We set off light, knowing we had a food cache on a prominent boulder not far from the fjord head but to our dismay we arrived there shattered and hungry to find it had gone. A lone trekker thought it abandoned and took it. We did have brewing gear but only one tin of corned beef to last the next twenty-five miles down the side of the fjord to town.

Rob took the can and prepared to cut it into three. I said: ‘Cutter gets the last

slice.’ Rob was incensed but eventually forgave me. But he never forgot.

Extracted from the first volume of Doug’s autobiography Up and About: The hard road to Everest.

Doug Scott was the first British person (alongside Dougal Haston) to summit Everest and has put up first ascents in mountain ranges around the world. He has climbed far and wide, on expeditions to Chad, Jordan, the Himalaya and Morocco at a time when such places saw few visits from outsiders, and is globally recognised for his daring and open approach to adventure. He’s one of the world’s most respected commentators on mountaineering and mountain communities, and is founder of the charity Community Action Nepal.

The first volume of Doug’s autobiography Up and About: The hard road to Everest is now on sale via Vertebrate Publishing.