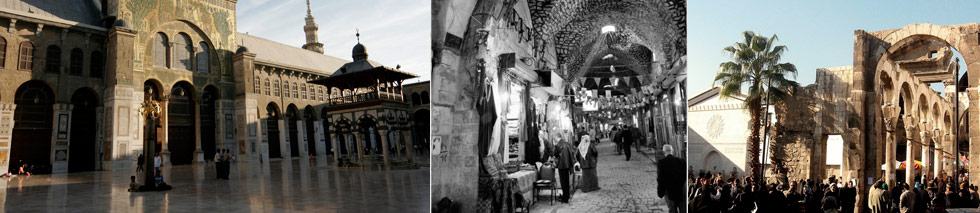

A little over a year ago, I spent a week in Syria. The country was as gentle and beguiling as I’d been told, but the whole trip now feels more significant than it did at the time. Travel is an ongoing process of discovery, so when lanes along which we’ve browsed bazaars and idly shelled pistachios fall under the grimmest of state suppressions, it gives more than just pause for reflection, particularly when our memories of the place are still so fresh.

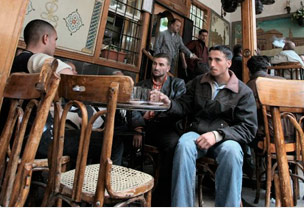

In Syria as elsewhere, the effects of the Arab Spring look set to be played out for years, likely decades. The country’s short-term future is unfathomable – certainly to me – and its current struggles have cast my experiences there, however fleeting, into a nervy new dimension. The two old brothers who sat with me in a Damascus cafe one evening, talking football in pidgin English and puffing shisha – how had their lives been affected? The teenager who insisted on buying me cups of cardamom coffee on the train out of Aleppo – what did he think of the situation? Had he seen this coming? And the toll of bodies rising weekly on the news – where did that fit into my £12.99 sightseeing guidebook?

The day I arrived in Damascus, I wrote in my notepad “Bashar everywhere”, in reference to the Mao-like omnipresence of posters and images of the president. The features of the London-educated, ramrod-straight leader gazed down from lampposts, shopfronts, restaurant walls and billboards. If this seemed telling at the time, it seems downright eerie now. Early the next morning, I pulled back my hotel curtains to see a group of government army cadets exercising on a parade ground. They were being instructed to forward roll through ankle-deep puddles. The group body language wasn’t wildly enthusiastic.