Life is all about decisions. Some of them are easy, some less so. This year involved some of the trickiest variety I’ve encountered in some while.

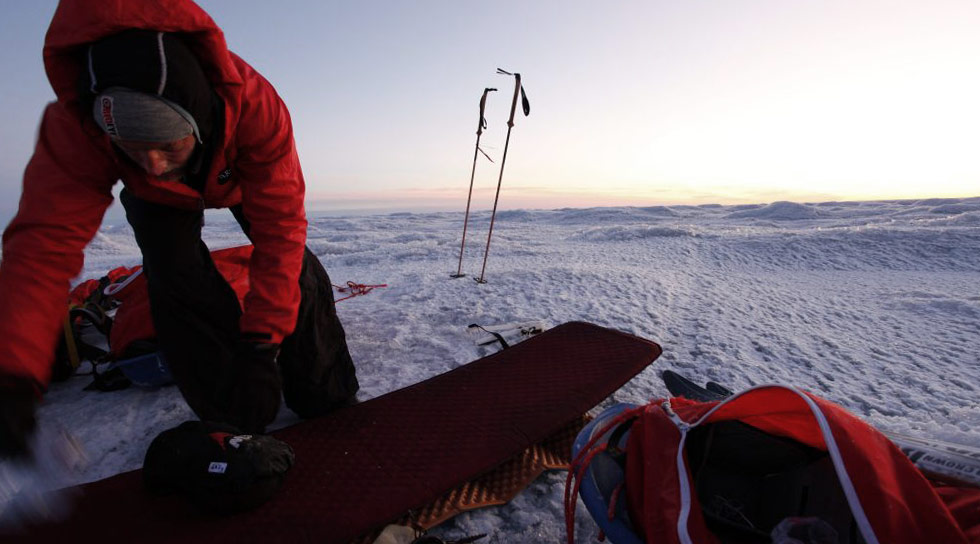

I started out 2011 with the intention of taking on a major challenge on the icecaps, the places where I ply my trade. Rather, the place where I’d ply my trade week after week if funding and commitments in the ‘real world’ allowed. Having reunited with a great team mate from years past, Andrew Wilkinson, known as Wilki, we set out a plan to challenge our resolve, fitness and technical skill. Unlike my usual expeditions, which concentrate only on getting to the finish-line and not against the clock, we planned to do just that: ski an established route and try to go faster than anyone had previously. Our stage was the Greenland icecap and the Nagtivit Glacier to Point 660 route, which had over the years become the ‘standard’ traverse from east to west.

The target was an insanely quick eight days and nine hours to cross the 350 miles of glaciers and icecap, climbing from sea level to 8000ft and back down again. Set by Odd Harald Hauge and his ferociously experienced and talented Norwegian team in 2002, we had a hard task ahead of us. In the past, the accepted time for the best conditions, flat surfaces and therefore fastest speeds was late summer, August or September. A lot had changed between the earliest fast crossings in the 1990s and early 2000s and so I knew I’d need to take a fresh look at the situation and avoid following like a sheep. Melting on the coastal regions of the icecap had increased massively in that time, causing a great obstacle to fast travel with melt streams and pools blocking a skiers’ path.

With this in mind, and having climbed the Nagtivit Glacier twice in spring conditions and knowing it like the back of my hand, I suggested April. With Wilki in agreement, we set about preparing with the knowledge that thick snow and more unpredictable weather could limit our chances. To break the record, everything would need to be perfect, especially since the 45-mile ‘ice-road’ that the previous expeditions had enjoyed on the west coast no longer existed. In past years the emphasis had been on sustainability. This time, it had to be on sheer speed. Daily average distances would have to be over 40 miles; monstrous considering the elevation we’d need to climb with sledges in tow.