Brittany – From the Coast

Sidetracked Uncovered

Written by Daniel Neilson // Photography by John Summerton

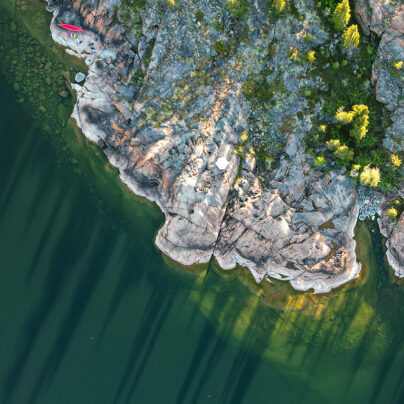

In the third of a series of articles exploring Brittany, we teeter on the edge of the Pink Granite Coast, exploring the beaches and cliffs, islands and inlets, and meet the people who live their lives by the sea.

‘I invite you to sit. Close your eyes. Take a deep breath,’ Christine Caurant says gently. I hear a splash in the water and the giggle of children in the distance. A bird squawks. Then, quieter, water laps the shore. The breeze pushes through the leaves, carrying the fresh, salty scent of the sea.

I lean over and pick up a rock, roll it over in my hand, and open my eyes. It’s a rough granite, clearly pink in colour, the hue of rock that gives the name to this coastline: Côte de Granit Rose, the Pink Granite Coast.

We’re on a short causeway near Trébeurden that in three hours will be under the water, cutting off Île Milliau from the mainland for another nine hours. And Christine Caurant is teaching us how to see again.

We’ve spent a week in northern Brittany, exploring the coastline, ducking among the Keremma dunes. We’ve walked some of the Sentier des Douaniers, the Customs Officers’ Path, and the Circuit des Mégalithes, and run the trails of the Côte de Granit Rose. It’s been fun, adventurous, busy. On our last day, we needed an invitation to slow down and sit. We’re not here to hike, nor to tick off viewpoints. But to see.

‘I seek out time to calm down and be present in nature now, but that wasn’t the case in the past,’ Christine says. ‘Now I revel in the time that I can take in the woods, by rivers or by the sea to take a breath, to slow down, and take a deep, blissfully concentrated dive into the natural world that’s right here around us.’

Christine is a naturalist, environmental educator, and a gentle kind of guide. Born in California, Christine returned to the land of her father and now lives here with her family. ‘I studied biology and environmental science at UC Santa Cruz,’ she tells me, ‘but always with a focus on the relationship between humans and the environment. That’s what fascinated me – the way we shape nature, and the way it shapes us.’

In 2024, she launched Explore the Trégor, a series of guided walks through the landscapes she knows best. Her offer was simple but rare: English-speaking tours in the hidden corners of Brittany, rooted in history, nature, story – and, thanks to her passion for yoga, being present.

‘My walks are about creating a moment of calm in nature, and sharing and exchanging stories about the natural world in which we’re immersed. Perhaps, in so doing, reminding ourselves that we are and have always been an integral part of the natural world… and we are all actors in protecting it.’

Île Milliau needs protection. It is, in a way, a 57-acre vignette of Brittany’s geology, ecology, and history both ancient and recent.

ON THE ÎLE MILLIAU

We begin by jumping across the rocks on the southern end of the island. Christine picks up a rock. It’s mostly grey, but marked by concentric veins. It’s the type of rock that geologists take their photo next to, and their explanation of it will probably blow the mind of anyone listening. The patterns, echoed across this end of Île Milliau – which consists of darker rock embedded in granite boulders – is evidence of rock that was formed between hot magma and cold metasediment. What makes Île Milliau so distinctive is how the island showcases both the smooth, weather-rounded granite boulders and the raw fractures of its uplifted bedrock.

We then step through deep time towards modernity, by which I mean a mere 6,000 years ago. We pause at a passage grave dating back to 4,000 BC. It’s a dolmen: a stone chamber built using the same local pink granite, positioned and aligned with astonishing precision. Though weathered by thousands of years, the structure still offers a clear view of how early inhabitants of this land used its geology not just for shelter or tools, but for ritual and remembrance. The entrance of the passage is aligned to the east, catching the first light of day, a possible nod to the sun’s rise and the spiritual significance of light returning to the world.

We continue to the far end of the island and step into the 1920s: the foundations of what was a pink villa known as Maison Aristide Briand, built by Mademoiselle Uro-Lalès in 1920. Mademoiselle Uro-Lalès was the mistress of the politician Aristide Briand, who served 11 terms as prime minister of France. For a while, the Parisian elite would descend to the island for some of her roaring parties. There may have been some frolicking in the bushes.

And then, for a final treat, Christine serves us some warm home-made elderflower cordial, a seasonal taste of Brittany. Every place Christine takes people – Goas Lagorn Valley, the beautiful Léguer river, the Guindy coastal stream – is chosen for its layers of human history, natural history, geology and story. ‘It’s like peeling an onion,’ she says. ‘I start with the plants. Then I notice the rocks. Then the old stories surface: Neolithic passage graves, Belle Époque holidaymakers, ancient Breton seafarers. The more you look, the deeper it gets.’

THE CAPE OF THE ROSE

The day before, we’d been a little farther east from our base in Perros-Guirec. We’d started at Ploumanac’h, a nearby village port on the northern tip of the promontory. It’s here where the pink granite is at its brightest and most fun. The 300-million-year-old granite is composed of three minerals: black mica, quartz and feldspar – it’s the iron oxide in the feldspar that gives this 25 hectares of granite its pink hue.

We intended a brisk walk, but with the tide out, we were waylaid by exploring the coves, clambering the rocks, wondering at the view and learning about the lively history of the region. We were walking the Customs Officers’ Path, created in 1791 – a walk named with impeccable accuracy but not nearly as evocative as the reality. From Trestraou Beach in Perros-Guirec, we headed west along the coast, the rock formations becoming ever more fascinating. It was a path used by customs officials to combat smuggling, particularly tobacco and hemp, and pillaging of the abundant shipwrecks. I struggled to imagine finding smugglers from this path, such are the intricacies of the rock formations. Occasionally, we passed the Ploumanac’h guérite, a stone sentry hut that would have served as shelter for the officers.

The Mean Ruz Lighthouse is made from the same rose granite, built in 1946 after the original was destroyed in World War II. La Masion de Littoral is an essential stop that offers innovative exhibitions alongside a cultural and geological history of Côte de Granit Rose.

South and it got busier around the Saint-Guirec beach, but through the maze of pathways and rocks we found the Chapeau de Napoléon, a pleasingly named rock formation. Its claim to fame? On April 3, 1943, the BBC broadcast a message to begin the armed uprising against the Nazis by the Breton Resistance fighters. The message was ‘Is Napoleon’s hat still at Perros-Guirec?’

By now, the evening light was slanting, and the rose rock enchanted. Time for fish and chips.

COASTAL BRITTANY

If we wanted, we could walk the GR34 (Grande Randonnée 34) along 2,000km of the Brittany coastline. The route follows the whim of the coast from Mont-Saint-Michel, a little east of where we were, around the entire peninsula. It traverses the Finistère headland, the Crozon peninsula, the Cornouaille coast and Pointe du Raz, South Finistère, the Gulf of Morbihan, and the Côte d’Amour to Saint-Nazaire. This is bucket-list stuff for French hikers.

Our journey was much shorter, but our week-long exploration afforded huge diversity in the coastline. Among the Keremma dunes, and the ‘Fantastic Rock’, we found the chapel of St Guévroc. At Pointe de Pen an Théven, with huge views over Kernic Bay and the Keremma dunes. And after a pleasant wander down to Pointe de Pen al Lan, we saw the island of Louët and the Château du Taureau, the restored Bull Fortress, built by the town to defend Morlaix.

As Christine said, ‘Every place has its own story.’

For more information, visit brittanytourism.com // @visitbretagne_official

Words: Daniel Neilson // @danieljneilson

Photography: John Summerton // @johnsummerton