Cache 23

Canoeing Across the Barren Lands

Written by Michal Lukaszewicz // Photography by Michal Lukaszewicz and Karolina Gawonicz

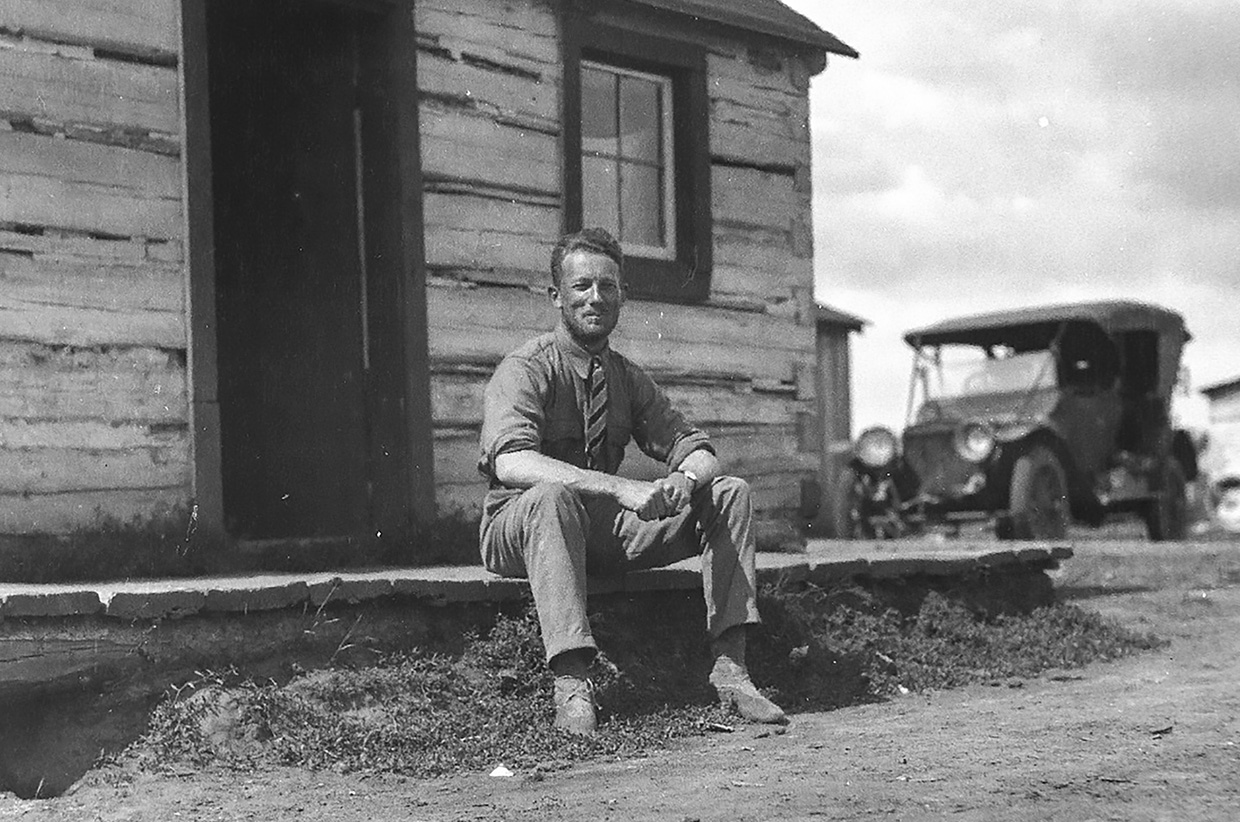

‘On a small island in the middle of Hanbury River we dumped 10,000 feet of unused motion picture film, and a £1000 movie camera. We were too starved to carry it.’ That short description, attached to a faded century-old photo showing an unassuming pile of rocks, has haunted me for two long winters.

100 years earlier

‘Do you think I will survive up there?’ James Critchell-Bullock asked his newly met companion over a glass of Scotch at Edmonton’s Fairmont Hotel. ‘You look like a gentleman. And gentleman can starve,’ replied John Hornby, who by 1923 was already known as Hermit of the North. The pair clicked instantaneously, complementing each other’s weaknesses. Bullock’s inheritance would pay for the expedition across the Barren Lands of Canada. Hornby had years of experience in the north; his speciality was to challenge the harsh environment to a duel, which always ended in a battle for survival. They arrived with a common goal: to secure the first motion pictures of musk oxen, which for years were thought to be extinct.

In 1924 they set off from Edmonton with two canoes, a few dogs, and minimal provisions. Their aim was to live off the land.

Hornby lived up to his reputation. The pair barely survived winter, starving for months in a frozen hole. The calendar page turned to July 11th, 1925, but out there the date could not matter any less. It was a hot, sticky, bug-infested afternoon in the Barren Lands, 500km from the nearest settlement. Bullock and Hornby kept pushing in their canoes down the Hanbury River. Exhausted, severely malnourished, they decided to lessen their load.

In the middle of the rapids, on a small island, they buried a cache containing motion-picture camera and spools of film. And Bullock took a photograph which, alongside his journals, was lost until 2015.

Inspired by their story, my wife Karolina and I decide to set off across the Barren Lands. Our goal: to not only find their cache, but also take a snapshot of a rarely visited world, one that changes so rapidly. For 64 days we will travel unsupported across the land called ‘a place where God is born’ by the Inuit – and we will come to truly understand why.

Unlike most canoeists, Karolina prefers the front seat. ‘It gives me the sensation of being merged with water, feeling at one with nature,’ she explains as we begin. I take the first few strokes into Great Slave Lake. Our red canoe weighs nearly half a tonne, and if we are to make it to Baker Lake by the end of summer we will have to share millions of paddle strokes.

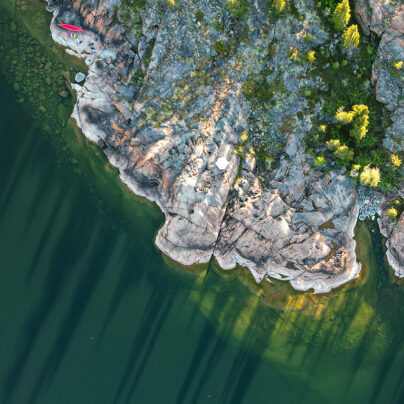

At first glance, everything surrounding us consists of just four elements: water, sky, rock, and spruce. Day after day, however, my senses tune in to the lake. Water undergoes constant transformation. In the sky, clouds fly as if on a conveyor belt. Rocks, on which we depend for sketchy campsites, vary from glacier-licked floors to spiky ridges crumbling from freeze-thaw. I particularly admire those spruces; each tells its own story of survival, battered yet proud.

Amongst the Dene People the lake is known as ‘Tucho‘ (big water), and it lives up to its name. We paddle across the bays, sometimes miles away from shore, cutting from one corner to another. Only the cry of the loon and sound of our paddles penetrate otherwise perfect silence. Karolina spots a fight overhead. It’s a pair of Arctic terns noisily chasing away a bald eagle, trying to protect their young from a much larger predator.

We finally cross paths with Bullock and Hornby at Pike’s Portage, less commonly known as the Gates to the Barren Lands. The small strip of sand at the east end of the lake doesn’t look like much, but it’s a test – and to pass you must make seven gruelling portages totalling 11km.

While I haul the 17.6ft-long canoe on my shoulders, Karolina grabs her 100L pack. It takes us four rounds back and forth to shift our supplies and gear. In blistering heat, knee-deep in mud, we slowly near Lake Harry escorted by gazillions of mosquitoes and the distant roar of musk oxen. I tell myself it’s not that bad; Bullock and Hornby needed 13 rounds to make it across with their equipment back in 1924. What strikes me the most about Pike’s Portage, though, is the change in vegetation. In only a few miles, the hardy boreal forest gives way to vast expanses of subarctic tundra.

Upon reaching Artillery Lake we can say that, at last, we’ve made it to the Barrens – a statement celebrated with an extra-strong coffee and bar of chocolate. That evening we strike camp early due to the forecast: wind gusting 71kph. Being windbound for two days is a godsend. Seeing my worry over lack of progress, Karolina says, ‘The land takes care of us. It told us to stop and we had to oblige.’

Next morning she pokes around our little island, smiling while picking not-so-ripe-yet berries. She follows with an hour of gentle yoga cut short by the smell of blueberry cake rising from a pit oven. ‘Life doesn’t get any better, does it?’ she remarks while we munch on cake, hiding from the wind behind our flapping tent.

Seeing the Barren Lands for the first time must have been a sobering experience for Bullock and Hornby. It was late August and both of them knew that autumn arrives in these parts rapidly, winter even faster. They needed a solid shelter until spring, but what dwelling could you possibly build in treeless, frozen tundra? Hornby suggested: ‘We can enlarge a wolf den. I’ve done it before. Those beasts know the best spots around here.’ Bullock wasn’t convinced. So they kept on going even farther across Artillery Lake as it gradually froze over.

Back in the present day, reaching the Barren Lands makes me feel instantly at home. We glide across crystal waters at a leisurely 4kph, but sadly the warm summery day sends me a wake-up call. Steady gas bubbles rise to meet our paddle strokes: bubbles filled with methane, a potent greenhouse gas released from melted permafrost after thousands of years in captivity. Karolina is silent in front as we paddle. It’s devastating to witness the rapid unravelling of this ecosystem – especially knowing the catastrophic impact it will have worldwide.

***

Bullock and Hornby picked the top of a sandy esker for their winter abode, and we want to find its location. Armed with copies of century-old photos, we hike a mile away from the Lockhart River, heading towards a magnificent spruce-strewn esker. It’s hard to imagine a more isolated place to overwinter. In summer it looks deceptively appealing – apart from the bugs buzzing their bloodthirsty anthem into our net-covered ears.

We slowly climb to the top through sand. Following the ridge, clues intensify: sea of caribou bones, old coffee tin, thick hand-sawn trunk. They lead us to the hollow where Bullock and Hornby sheltered, and an old photograph finds its perfect match right in front of our eyes. Karolina turns and sweeps her hand, encompassing the landscape. ‘I’m glad we never planned to live off the land here,’ she says. ‘Look around and imagine it frozen, in darkness, struggling to choose between a pen and a madman for your best companion.’ Suddenly we find extra motivation to reach Baker Lake by the end of summer.

Portages take us across the divide separating MacKenzie and Hudson Bay watersheds. From now on we follow the Hanbury River, a classic pool-and-drop system littered with Class 2 rapids. The water levels are low; our canoe does more scraping than floating. Winding lakes bring a welcome respite, providing us with predictable paddling and just enough wood to pan-fry fresh oily trout over fire.

When Bullock and Hornby travelled down the Hanbury only moss was available for cooking. The fact that we could spot young spruce trees nearly every day proves that the treeline is shifting further north. With changes in vegetation come changes in wildlife. A few eskers produce sightings of nesting bald eagles – an iconic species thought to only breed in boreal forest. The Barren Lands might not have changed much for 9,000 years but they certainly will over the next century. Rising temperatures will attract more species from the south, invading the tundra’s delicate ecosystem.

After six weeks of paddling and portaging, we battle headwinds on Lac du Bois – where Bullock wrote his last journal entry before taking the photo of the cache back in 1925. Combining photograph with Bullock’s journals and modern satellite images, we have picked our best-guess coordinates on a small island in the middle of Grove Rapids. All modern-day paddlers portage around them over the esker, which provides good footing. It explains why nobody has stumbled upon the cache site over the past century.

However, when we reach Grove Rapids neither of us can be bothered with the cache. Karolina collapses on the sand, extending her sore hand to pick blueberries and load them straight into her mouth. I can barely feel my arms after paddling against the wind for hours. ‘I don’t want to obsess with progress, but should we really waste energy and time searching for the cache? We don’t even have the tools.’ My tone and mood are gloomy. ‘Are you serious?’ Karolina replies. ‘This is not like you forgot something from the shop and you’re not bothered go back. This is now or never!’ She rolls towards our food bag. ‘Let’s have that leftover bannock with tea. We can’t think straight until we’re fed.’

Once nourished, we walk towards the island, but rocky walls and a rushing river put it off limits. We climb to the highest point in the area for one last look before retreating to camp. From the top we can see the panorama of the river. I look at the picture again. ‘What in this photo would not change in 100 years?’ I ask. In the background of the photo, very blurry, I notice a cube-shaped erratic boulder. Suddenly, a large erratic cube appears in my binoculars. There is a small lake in the background. The distant scene looks like a fragment of the photograph! All we have to do is determine what angle the photo was taken from. This leads us to a small peninsula downstream.

Half an hour later, a mound of boulders in view, the scene 99 per cent matches Bullock’s photograph. ‘What do you think?’ I ask Karolina. ‘This is it!’ she replies before expressing herself in action: first she looks around checking for bears; second a big rib-crushing hug; third an odd jump, screaming in pure joy; fourth she regains focus and cracks on with the job.

We’ve begun to clear soil from underneath the boulders. Fatigue gone, I feel chills rushing down my spine. Somehow we’ve found the rocks that Bullock and Hornby placed with their own hands 100 years ago. Little man-made pieces start to appear between our fingers. Crushed rusty pieces of metal, fragments of canvas tape, a piece of wood. Finally, the largest of the fragments – a round piece of metal, clearly part of a cine film can. After removing the soil, there is nothing left to dig into – we’ve reached solid rock. No trace of the missing camera.

We sit down to rest, fingernails grimy with black soil. What happened to the camera? Surely it would resist a century of decay. Then we realise what had most likely happened. James Critchell-Bullock never returned to the Barren Lands, unlike John Hornby. In 1927, Hornby and two companions completed the same route along the Hanbury River. The three men built a hut in the Barren Lands where they died of starvation a few months later. Hornby always relied on others for financing; after all, it was Bullock who paid for their joint expedition. Only Hornby knew where the cache was buried – a cache that held a valuable camera. Our theory is that John Hornby removed the camera himself, hoping that he would be able to sell it when he returned from the Barren Lands. We have no other explanation.

So what, some might say, that you dug up some garbage in this remote area? For us it was a puzzle solved after 100 years. It was about a connection with another human being. While reading Bullock’s letters, we felt his pain and dilemmas. When travelling through the Barren Lands, we experienced them first-hand. Reaching the cache site, touching the boulders placed by Bullock and Hornby, we felt a strong connection with them through the land which allowed us to experience similar feelings.

Leaving the Barren Lands was a deeply emotional experience for both parties. Bullock and Hornby regretted their return to civilisation, fantasising about the land where existence is felt so acutely, where freedom goes beyond the false definition of escape from society. For Karolina, reaching Baker Lake brought tears to her eyes. She knew the days of cloudberry-crowned morning porridge and evenings spent listening to howling wolves were gone. For me, the end brought a sense of loss – a peculiar period of mourning. Because what we saw and experienced is sacred, guarded by a lack of roads and airports, unrestricted by dams. Yet, as the bubbling methane and northward-marching trees prove, it is heading for disaster.

First published in Sidetracked Magazine Volume 30

Archive photos published thanks to John Hornby’s son, Mowbray.

A documentary, Cache 23, is coming soon.

Written by Michal Lukaszewicz

Photography by Michal Lukaszewicz and Karolina Gawonicz