Desert of my Dreams

Written by Vedangi Kulkarni // Photography by Sayandeep Roy

‘The floor is lava, don’t unclip your foot because your shoe might burn,’ I tell myself. Years of riding a mountain bike may have taught me to look ahead rather than right in front of my wheel, but today it is not helping. I am staring at a 20 per cent climb and willing myself to not stop. Nobody would blame me for walking up this. But after about 23,000km of cycling around the world, my ego simply will not allow me to do so. If there ever were a time to convince my mind that I am competent at this cycling thing, then this is it.

Sweat is dripping all over my phone and bike computer as I count from one to 10 over and over again. The climb gets steeper and my willpower is dwindling. There’s no point stopping where there’s no shade, so I decide to push on. Then the car, driven by an enthusiastic Omani driver called Aqeel, comes down the hill carrying my parents and my photographer friend Sayandeep. My mum looks out of the window and asks me what’s taking me so long. I just nod, exasperated, and think, She’s right, Vedangi. What is taking you so long?

Later, I spot a huge canyon up ahead and decide to stop there for lunch. Some food would do me good. The car stops too. I don’t say a word to anyone. I’m sick of riding my bike. Actually, maybe I am just sick. A tooth infection has left my cheek swollen from the inside. My heart rate is in anything but the zone two or three that I promised myself. My brain is overwhelmed with emotions, being around family after spending the last four to five months by myself around the world. And don’t even get me started on how embarrassed I am to have failed at the same goal for the second time in six years.

Cycling around the world in the fastest women’s time is an ambition I set for myself at the age of 18. Only a few months after I’d moved to the UK from India I went for an accidental ride from Bournemouth to John o’Groats, and got inspired by a book I read in my lonely moments along the way. The first time I finished riding 29,000km around the world, I had just turned 20. I’m 26 now and I am just around the corner from finishing this second ride. But for now, all I need to do is to get to the top of this climb.

‘You’re not 19 any more; you have got to be better than this,’ is something that I have told myself over and over again. It’s easier to be hard on myself than blame my circumstances. To be completely honest, fate hasn’t favoured me much in that respect. At least I didn’t get chased by a bear or mugged at knifepoint this time.

When I get closer to the top, the road is flat and I find a magical tailwind. My inner weatherwoman knows that these conditions won’t last long. I must make the most of this. But I spot a sign for a viewpoint and my biggest weakness takes over. In come the excuses: what’s the point of cycling around the world if you’re not going to stop and enjoy the view that you climbed so hard for? So, of course, I have to pull over.

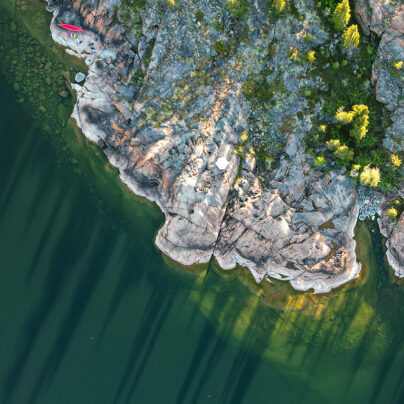

What I see is something I’ll still be talking about when I’m 90. I’m certain that all shades of ochre are visible in that valley. I marvel at the layers in the rock and quietly wonder how many centuries of erosion it must’ve taken for those shapes to be carved and those colours to show up in that exact pattern. In moments like this, I refuse to be rushed. I take this view as the universe’s big hug – a reward for managing to make it to the right place at the right time. When I feel like I’ve taken it all in, I am back on my way. There’s a slow teardrop trickling down my face but I’m far from anybody who could see it. This moment can stay a secret between that beautiful view and me.

***

‘Do you have anything savoury in the car? Even a sachet of salt would do!’ I desperately shout to my parents. They seem to have nothing apart from chocolates, which is not what I’m looking for but food is food. I grab a couple of bananas and a Dairy Milk ,and off they go until the next time Sayandeep needs to take a photo or somebody wants to check on me. This could be 20 minutes or two hours. I patiently wait until my Cadbury bar melts so that I can pretend it’s Nutella.

This whole cycling-around-the-world thing has convinced me that I’m as delusional as they come. As I ride along a flat road with a crosswind, I find myself so salt deprived that my brain doesn’t seem to be functioning at its full capacity. I look up from my aerobars, trying to find something in the distance. There’s nothing. I feel tiny, consumed by the vastness of this desert. This is a great feeling when I think about life in general, but right now I am restless. So I look back down and tell myself I’m cycling up Khardung La in Ladakh through a blizzard – pretending I can’t see the pass in the distance, but knowing if I keep going I’ll eventually get there. This desert is very far from Ladakh. But in my head, there will be a town, a gas station, a lay-by or something. That will be my Khardung La.

A car passes by, waving at me frantically. There are about six kids inside, two of them cuddling their mother on the front seat while their father drives. They stop me and get out of the car. In Mongolia, this normally meant that people just wanted to take photos with me. Not this time, though. The driver is a man with a plan. He gives me six packets of cheese puffs and four bottles of water. I thank the whole family profusely.

When I see the parents-plus-media car next, the packets of cheese puffs have all been finished, there are crushed water bottles in my pockets, and I have a huge smile on my face. It’s funny what some salty food can do to my mood! As it turns out, my Ladakhi mountain pass wasn’t a gas station in the Omani desert, it was six packets of cheese puffs.

After days of battling a strong headwind and a mild but annoying crosswind, I finally think I will have a full day of nothing but tailwind. This is exciting for two reasons: getting to the speed I know I’m capable of, and finishing off the desert section. However, I’ve been enjoying drawing parallels between this desert and the ones I’ve cycled across in Australia and Mongolia. The best part about riding through a desert is that you can be fully present and really absorb the nothingness around you, but you can also build up these wild scenarios of places you’ve been before, or even challenges you haven’t undertaken yet, imagining what it’d be like to finish that seemingly impossible thing. It can be a desert of your dreams.

This section has a lot of police presence. Every now and again, there’s a sandy road that goes off about 50km deeper into the desert, leading to some petroleum plant. The police presence is to safeguard these places. What is beyond me is why the police would ever consider me as a threat. As I ride along, minding my own business, I hear a loud siren. It couldn’t be more obvious that it is intended for me. Two policemen get out of the car and ask me what I’m up to. I don’t feel threatened by them because I know I’m not doing anything wrong.

‘Do you realise that this road doesn’t have a shoulder and the cars are going really fast?’ one of them asks me. My instinctive (and sassy) answer, which I thankfully keep to myself, is ‘Well, how the hell do you think I got here?’ Instead, I let them know that I am, indeed, aware of it and I have cycled a really long way, not just that day but in the last few months, so I will be just fine. They nod, obviously unconvinced, and then let me go after following me on Instagram and taking a photo together.

As much as I hope that this is a one-off incident, it isn’t. This happens again. And again. My patience is wearing thin. But there’s no reason to be rude to them. I’m aware they’re just looking out for me. So I just say the same thing every time and keep riding.

It turns out that they seem to have a problem with me riding my bike on a road where big vehicles are passing by quickly. That, and all the night riding. It’s challenging to explain to the police how it feels safer to ride in the dark because I can see a car from miles away and there’s less traffic. Also, I’m lit up like a Christmas tree and wearing bright clothes that make me very visible. In many of those moments, I wished that I could get the police officers to ride a short section with me, and show them that not only is what I’m doing safe but also that the drivers in Oman, their own country, are very respectful.

***

Just before I leave Hasik, a village along the east coast of Oman, I head into a restaurant for breakfast. As I find a suitable place to park my bicycle, an old man starts interrogating me.

‘Where are you from?’ he asks. I tell him I’m from India. Then comes a question that I have been asked at least 50 times on my ride around the world: ‘Are you married?’ I tell him I am not. As it turns out, he wants me to get married to someone he knows. ‘A good Omani man will want to have kids with you,’ he tells me. I laugh because I think it’s a joke.

I tell him that I like to ride bikes so that’s what I will do. But later, as I leave the restaurant, I am bursting to turn back and tell him about every solo expedition I’ve done. About the women in my life who have done incredible things out in the world by themselves. I’m angry and sad. I’m angry because of his audacity to assume that I’m incapable of looking after myself without a man next to me, and sad because he probably doesn’t see much potential in the women in his life.

As I turn a corner onto the main road, I find myself riding next to the turquoise sea and my anger melts away. If I let myself stay angry, then this is all I’ll think about when I’m 80 years old, sitting by the fire and remembering the time I rode my bicycle through Oman. Of course, I can’t let that happen.

I have been looking for an opportunity to stop and have a brief nap for the last couple of hours. The road is straight and there is no shade in sight. The wind is running the show and I’m not liking it one bit today. Far up ahead, I see our vehicle parked on the side. Actually, I’m hoping that it is ours; there’s no way to be sure until I’m close by. My morning so far has consisted of exchanging some seriously harsh words with myself. This is mostly because I can’t tell if there really is a headwind or if I’m just not feeling very fast or strong. My self-esteem has taken a bit of a hit lately, but my goal is forward progress and part of me knows that this is going to fix me. I put my hand in the plastic bag hanging on my aerobars and grab a handful of grapes. It’s a hot day and they’re a bit squished. Nothing beats grapes, though.

I ask myself, ‘If Vedangi from 10 years ago or 10 years from now looks at what this present version of me is up to, would that make her proud?’ Normally, this question puts a stop to self-doubt. Loaded question, but it’s a sure-fire way to bring a chronic overthinker like me back to her senses. I look around. I’m riding through a desert. My fourth desert of this big ride. A lot of things had to go right and even more had to go wrong to bring me to this exact moment. I think of every moment in Oman that’s made me go WOW – the sky, the sea, the mountains, the desert. I can’t help but smile.

Turns out, the car parked on the side was, indeed, ours. I pop my bike against the railing beside it, take my helmet off, and lie flat on the road with my legs up against the railing. I close my eyes and let the happiness sink in. I chose this adventure and it is living up to every single definition of that word.

First published in Sidetracked Volume 32

Vedangi Kulkarni was attempting to be the fastest woman to circumnavigate the world on her bike, solo and unsupported. Her Indian passport meant that she had to choose an unconventional route for ease of visa procedures, which added logistical complications. When she realised she wasn’t on track for the record any more, she had to rethink her approach. In April 2025, Vedangi completed her journey – lasting 270 days and a total distance of 29,030km.

Written by Vedangi Kulkarni // @thisisvedangi

Photography by Sayandeep Roy // @sayandeep.roy_